Kelbly Atlas Tactical rifle with Harrell’s tuner brake and Lapua ammo during testing.

Table of Contents

– What lead to this article

– Background on tuning

– About the Harrell’s tuner brake

–Testing procedure

– Data Analysis

– Conclusion

– Acknowledgements

What lead to this article

Everybody who reloads knows that some combinations of powder amount, bullet seating depth, bullet, and case work dramatically better than others despite being loaded on the same equipment to the same standards of consistency. This is to say, quality being the same, dramatically different results are obtained from different loads. Finding the right combination is termed load development and traditionally involved varying powder charge, seating depth, and if things did not go so well, often what powder and bullet were used as well.

Since barrel tuning became a thing, many have simply added it as the final step in the load development process such that they work up the best load they can and then tune it further with a barrel tuner. However, I have also known some people who have stopped much of that traditional process and now put together the bullet, powder, and velocity they want and tune the barrel to the load using a barrel tuner and have had success with this new strategy. Barrel tune is evidentially the primary factory in whether a particular high consistency hand load performs well in a rifle or not. This new method of tuning a barrel instead of a load is appealing since you get to keep your first choice in bullet, powder, and velocity. Added to that, proponents claim they can easily and predictably adjust the tune for significant temperature changes. These ideas were marinating in the back of my head during my reviews of the Kelbly Atlas Tactical and Mesa Precision Arms Crux rifles last year. I used only factory ammo and thought that I noticed improvement in rounds while using a magnetospeed chronograph (which attaches to the barrel and changes the tune) with some rounds (Lapua in the Kelbly) as well as degradation of some other rounds (Hornady in the Mesa Precision Arms). The differences were small and could easily have just been noise in the data but I got to thinking that maybe they were indicative of barrel tune being a major factory in whether a particular rifle liked a particular ammo or shot poorly with it. Maybe, like a reloader picking the load he wants and then tuning for it, a shooter could also pick the quality factory round he wants and then tune for it instead of trying a box of a lot of things and seeing what shoots best. Certainly, tune is in play with factory ammo just like with handloads, the question is just how much of a factor is tune in the overall performance of a particular rifle with a particular factory load. After all, there is much more inconsistency in even the best factory loads than most handloaders will have. Conversely, factory rounds are often tested for how well the perform in a variety of rifles and so may be less harmonically active than handloads that have not such testing. Nobody seemed to have done testing on this idea so I set out to do so. I chose the conventional steel Krieger barrel Kelbly .223 for this testing instead of the Proof carbon barrel Mesa Precison Arms Crux 6.5CM because Proof carbon barrels are very different harmonically than conventional barrels. Based on my experiences as well as what the physics predicts given many of the current tuning theories, my belief is that proof barrels are less harmonically lively, so tuning will matter less. Also, Proof barrels should vibrate at much higher frequencies making their nodes narrower, closer together, and probably harder to tune for.

Background on tuning

Despite being a concept that has been around and in production some 600 years there is quite a lot about the rifle that is not at all settled science. The concept of “Tuning” is one of the better cases in point. I will give the simplest possible explanation of this here as well as link to a few more complete but also conflicting theories of what is actually going on. It’s a fun rabbit hole to jump down if you like geeking out on the less settled theoretical aspects of accurate shooting.

In the simplest terms, the idea of barrel tuning posits that barrels vibrate as the bullet travels down them and that these vibrations result in some parts of the barrel moving faster than others. The faster the crown is moving, the more erratic will be shot dispersal will be. By moving a weight at the end of the barrel you can effectively change where the fast and slow moving parts of the barrel are and tune it such that the crown is at a slower moving place. How exactly the barrel is moving is something nobody agrees on but this does not much change how you go about tuning it.

Bill Calfee first introduced the idea of barrel tuners in a 1994 article in precision shooting. In that article, and in the 10year anniversary follow up that he did in 2004 he posits a theory of how it is that rifle barrels vibrate during the course of a shot. Rather than paraphrase his work, I will simply link it so that those interested may benefit from the words of the originator.

Bill Calfee’s “I’m Feeling Those Good Vibrations, AGAIN!” 2004:

Somewhat related to the Calfee theory of barrel harmonics (it is based on continuous vibrations though incorporates more modes of vibration) is the Purdy Prescription for how to tune a barrel. The Purdy Prescription is a method for determining a tune that is based on a theory of how barrels vibrate.

The Purdy Prescription for barrel tuning:

More complicated theories about the nature of how barrels vibrate during a shot have also been proposed. Probably the most interesting of these is that of Former Lawarence Livermore National Lab engineer Al Harrel who performed Finite Element Analysis simulations of the whole rifle / cartridge system throughout the entire firing cycle. These simulations have produced some pretty interesting visuals of the firing process as well as some different thoughts about why it is that tuners work. Most notable about Al’s work is that it accounts for the rifle barrel not being an isolated continuous system during the course of the shot as the bullet and expanding gas continually act upon it. This makes it what I would call a driven, as apposed to continuous system.

Though all these theories disagree with each other in some very basic ways on how barrels vibrate during a shot and even how best to go about tuning them, they share the conviction, now quite well supported with competition wins, that barrel tuners work, can significantly improve group sizes, and can allow the shooter to more easily keep his rifle system operating at optimum tune through a variety of temperature ranges by changing the tune of the barrel instead for the amount of powder in the cartridge.

About the Harrell’s tuner brake

There are not a whole lot of options for tuner brake combo’s that both fit 5/8″-24 threads, and the larger muzzle sizes of precision rifles. In fact, I only found one. Despite the paucity of other choices, I am pleased with the product. Harrell’s precision is quite well known in the benchrest community for making very accurate volumetric powder measures (yes, I have wondered for some time if they could prove accurate enough for long range shooting provided a small grain size powder is used but that is a test for another time) and also for their portable reloading presses. At the benchrest matches I have attended virtually everybody uses the measure and many the press. The powder measure and press mount to your bench with a clamp and are therefore easy to take to the range with you to develop loads in an efficient manner. Of course, what we are trying to do in this article is to find out if we can tune factory loads effectively enough to avoid having to do all that load development stuff. The irony of this is delicious. The Harrell’s tuner brake shows the clean, high quality machining I would expect and is generally a pretty nice looking unit. At $90 it also appears to be priced on the benchrest price scale and not the tactical one. Say what you will but the tactical tax is a real thing.

There are a few features that the Harrell’s tuner brake has that I like and one that is less desirable. The brake uses a jam nut adjustment lock system to secure the adjustable weight collars. This is greatly preferable to me over set screws which require a tool to manipulate, have a greater tendency to come loose, and can bung up the thread they run on if over tightened or not tipped with a soft material. The marking system on the brake for keeping track of your settings is quite well designed. The brake contains markings on the body for each complete revolution. These bear the designations 0,50,100,150 as well as 10 markings on one of the weight collars per revolution. Therefore, a simple single number is produced for each possible setting when the markings are added. For instance, if the reading on the brake is 100, and that of the weight 7, your total setting would be 107. Very easy to record and keep track of. The only major downside I see to the design is that it is radialy symmetric and therefore exhausts gasses in all directions. It is nice that you don’t have to index it but you western folks are going to kick up some dust. I’m from Ohio, so for me, this is a case of somebody else’s problem.

Since the website lacks some detail on the specifications I’ll give you my measurements here:

– Total weight 7oz (2.10oz in the movable weights and 2.9oz in the stationary brake.)

– Inner diameter of weights .9930″ (will only work with barrels with a muzzle smaller than this)

– Overall adjustment travel: 15 complete revolutions ~.47″

In my experience using brakes I have never been able to effectively note some being dramatically more effective than others at recoil reduction. However, some are easily noticeably louder than others and I hate them. This makes since because some, very popular, rear angled brakes actually increase sonic energy dumped on the shooter by almost 10x others. The Harrell’s tuner brake is not one of these earsplitting units. It was not loud and the recoil was negligible (though a heavy .223 with a squishy recoil pad and a brake is always going to be.)

Testing procedure

Without question, devising a testing procedure was the trickiest part of this article and frankly it is entirely possible I got it all wrong and could have achieved better results. It is also probably the case that I was simply asking too much improvement from a tuner and this effected my procedure design. My goal was to come up with a procedure that would be plausible to perform for the type of shooter that might be interested in tuning factory ammo. By this I mean the guy with enough knowledge and experience to be interested in improving on factory ammo but not enough of time or commitment to be solely loading his own ammo. So, the procedure can’t be to fire 5 rounds at each of the 150 numbered positions in the tuner over the course of several days and then go back and do a second and third group at each of the 5 previous settings that had the best result. Realistically, if you are willing to go through all that than you would be already loading your own ammo. The procedure needs to be something that could be done in a few hours with 2 or 3 boxes of ammo so you can still shoot some steel at distance that day. This meant that I was really looking for tuned groups that looked around 50% better than untuned ones. If the difference between tuned and untuned wasn’t that stark I would consider that tuning factory ammo was probably not something worth pursuing.

There are a lot of knowable, calculable things you could know about tuning, and your personal shooting platform that would help but which you might not know. For instance, the approximate distance from one in tune setting (node) to the next on the tuner would be helpful. This would certainly vary with barrel thickness and length as well as with the weight and thread pitch of your particular tuner but a rough equation could exist. It does not however. You might also know about what group size you could plausibly expect from your rifle and ammo. Perhaps you have fired it un-tuned and have a baseline that you seek to improve on.

From talking to a few industry experts I expected a node to node distance of between 0-2 full turns (000-020 in tuner setting numbers). I also expected to see evidence of “getting close” to a tune on settings adjacent to the ideal one. For this reason I elected to start with the tuner screwed all the way in at 000 and go up in increments of 002. I had shot the rifle untuned with this exact lot of Norma ammo and with a different lot of the Lapua ammo and so knew I was looking to better ~.5″ @100yds with the Lapua and ~.7″ with the Norma. For success I was really expecting to see the worst mid node groups significantly worse than that and the on node groups to be significantly better.

So, the procedure was to start firing at each interval. If the group started out good, keep going to 5 (initially I went to three with the intent to circle back but later went all the way to 5). If the group got blown, I would move on the next interval. Of course, when many groups are only 2 rounds you could easily miss a node from one flier round. Fliers are not uncommon in factory ammo. Similarly a clean, 5 rd group could just be random good fortune. As such, groups that looked good would be investigated by returning to that setting later on. For example, there are three 5 round groups later in the Lapua testing on the 012 setting. It was a setting that looked good, until it looked terrible. In the end, if I found a solid node, I would fire a set of four 5 round groups to compare with that ammunitions previous, untuned, performance. This never happened. Every roughly 20 rounds, at a time I was also between groups, I would also stop to allow the barrel to cool down and to clean it. One fouling round was fired before beginging again. The conditions were ~72 degrees with mixed clouds and sun and with low, 0-5mph wind from 12 o’clock. There was essentially no mirage as well. You really couldn’t have better conditions.

Data Analysis

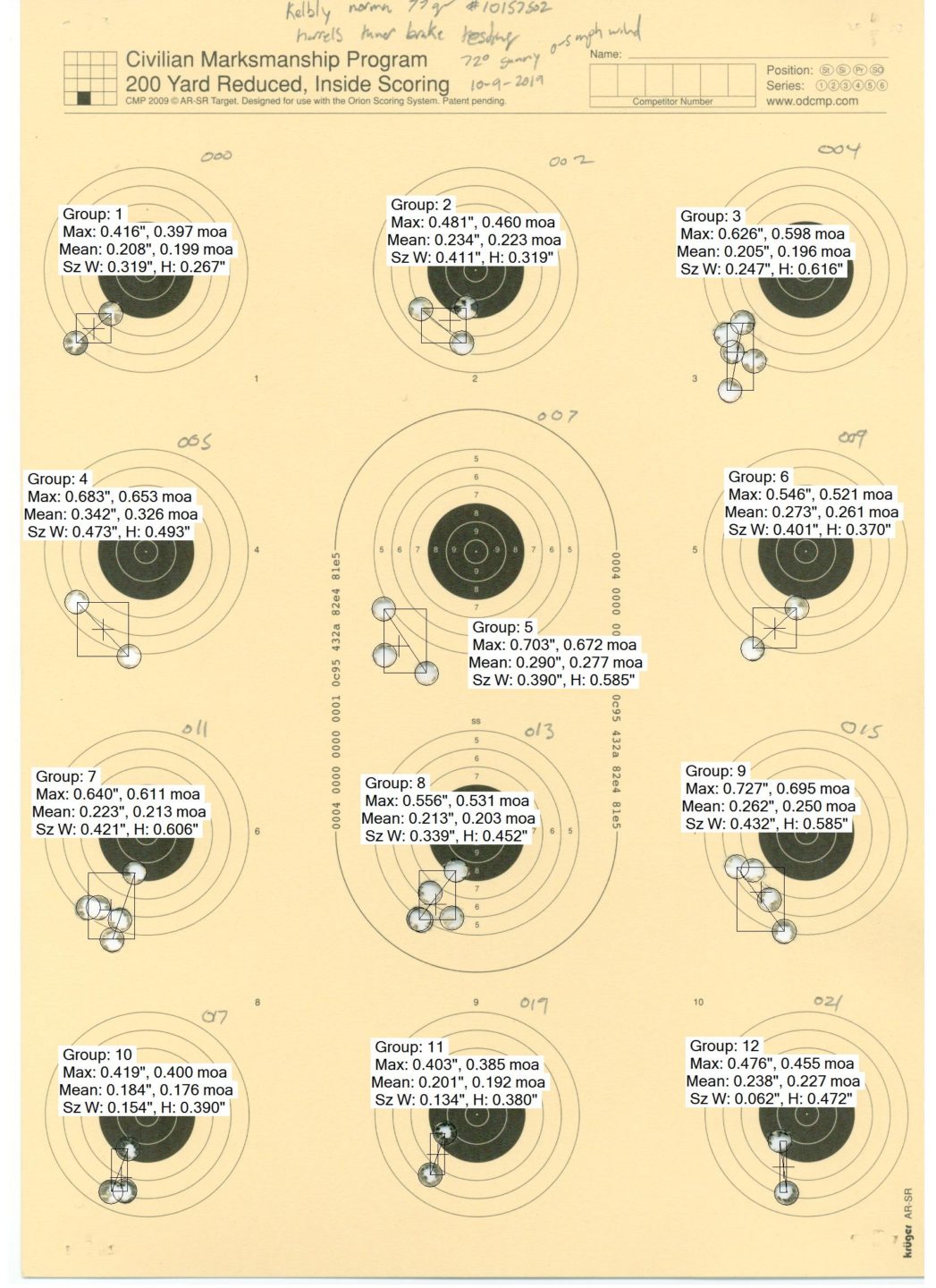

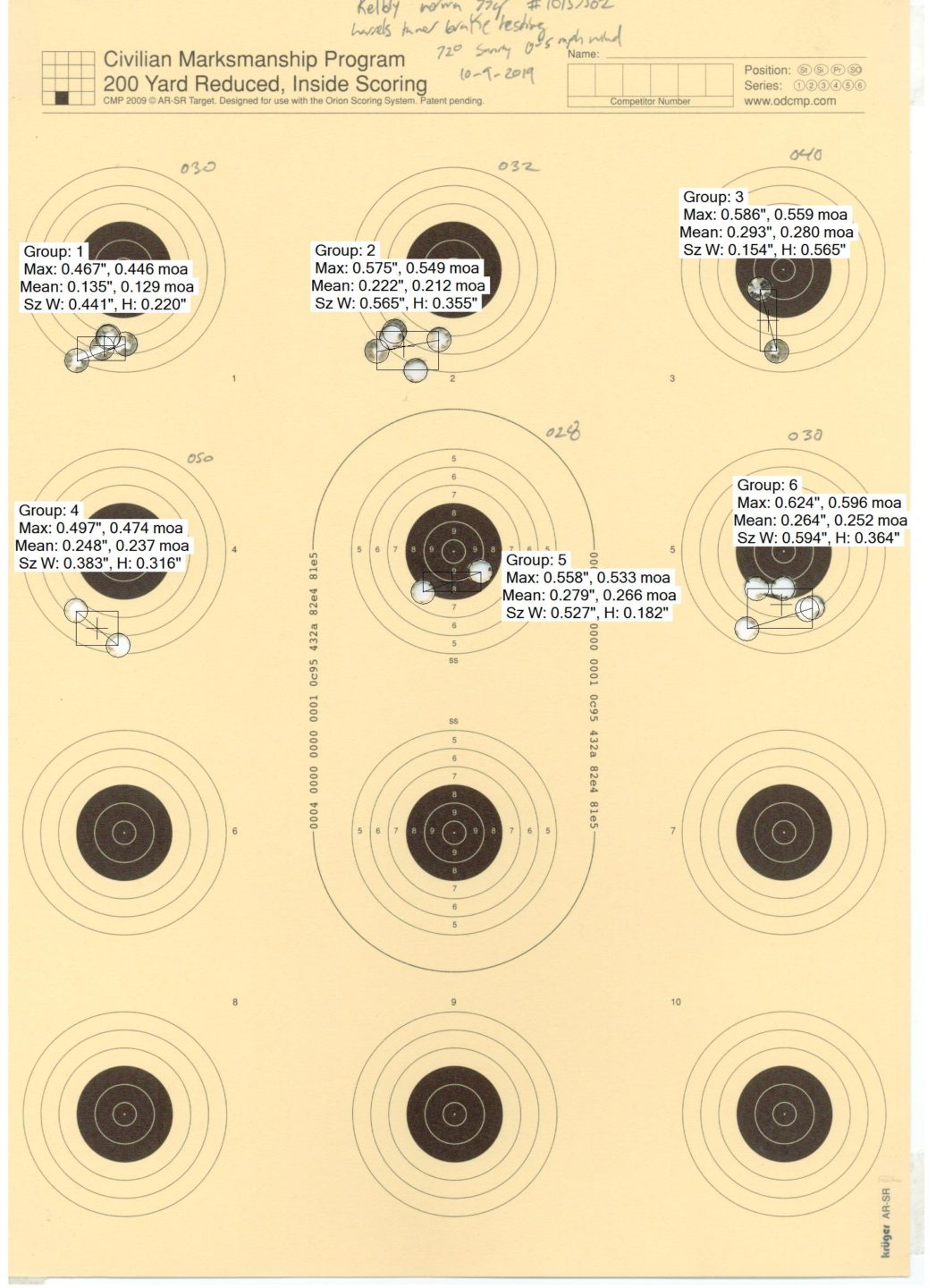

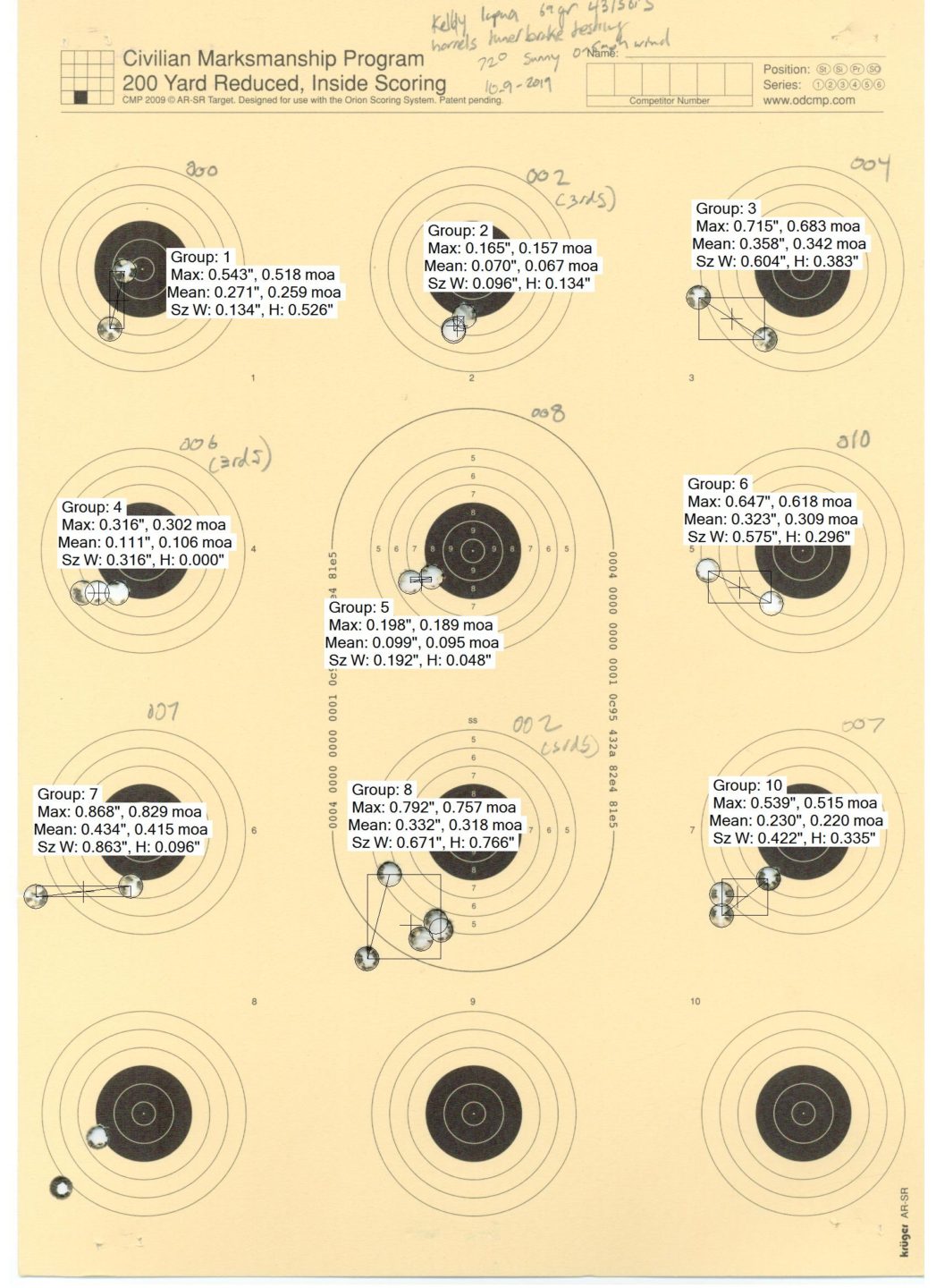

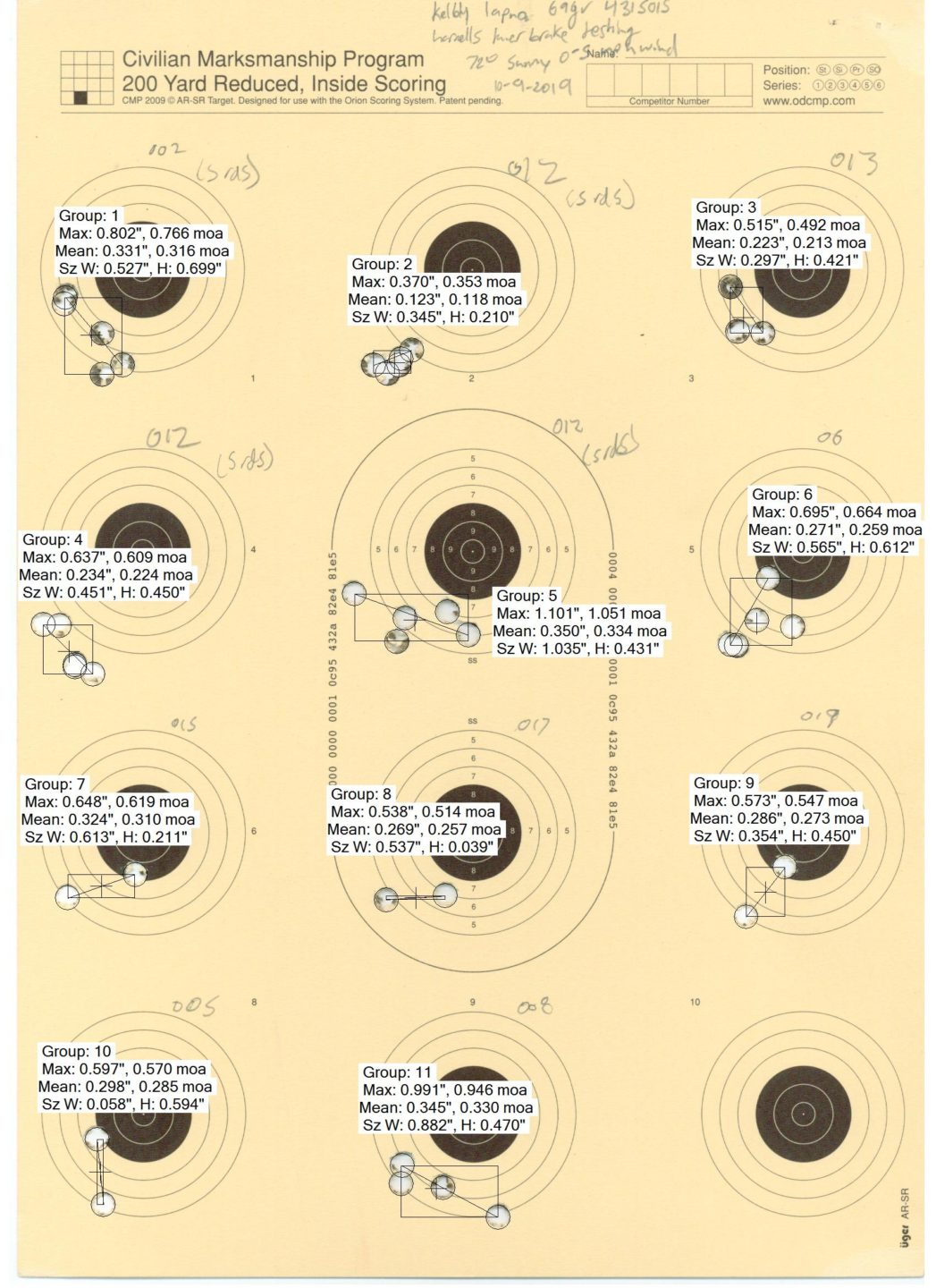

Below are all the targets fired and the max group sizes, mean shot to shot distances, and horizontal and vertical max distances (important for one of the tuning theories and procedures.) Keep in mind when viewing these targets that the Group number is not relevant, the analysis program just adds this. What matters is the hand written tuner setting number in the upper right. Many settings are returned to in later targets.

Norma ammo data

I’m going to start with the Norma targets though they were fired second because, having gone though the procedure once, I had improved my methodology, went out of order less and returned to settings less. It is therefore less confusing to the reader.

The reader will note that there are five settings for which 5 round groups were fired. These are 004, 007, 008, 030 (2 groups) and 032. The reader will also note that most of the groups that didn’t get to 5 rounds would easily fit with those that did. It is as if they were going to be similar groups, but, with the furthest out two rounds fired first were just not allowed to progress further. No tuning pattern is in any way apparent to me in this data. Furthermore, when compared to the previous groups fired bare muzzle with this ammo and rifle they are not dissimilar. Though collectively their max extents are better (.580″ vs. .706″) when looking at the more important average distance between each round in the group they are almost the same (.231″ vs. .243″) How nice and tidy this data looks. Changing tuner settings does not appear to have had any significant effect on group sizes positively or negatively

Lapua ammo data

In contrast to the clear lack of any discernable pattern in the Norma ammo, in tuning the Lapua ammo I often felt like I had found something only to have it evaporate. Like chasing shadows. The first 3 rounds at setting 002 were absolutely stellar at .165″. That was only the second group I fired and I thought “hot damn this tuning thing is slick and easy”. However, when I revisited this setting it produced five round groups of .792″ and .802″. Clearly nothing special there. Similarly, the first five round group at setting 012 came in at .370″. Unfortunately, the next two at that setting were .637″ and a truly ghastly 1.101″. What was most tantalizing about this, in the fully Grecian mythological sense, Is that many times the first couple rounds at a setting would be absolutely stacked on one another only to blow apart into a genuinely terrible group upon further investigation. I kept thinking, well, maybe I should go back and look again. It looks like maybe there is something at such in such setting. Every time I would go back though, I would find nothing. Unlike the Norma ammo, which was the same lot I had previously tested in the Kelbly this Lapua was a new lot. The first lot was #1520 and this is #009T. As such, the previous data that I took on performance without a tuner is not really comparable to this. All I can really say about that is that the previous lot performed significantly better in this rifle than this lot did (.581″/.198″ vs. .733″/.274″)

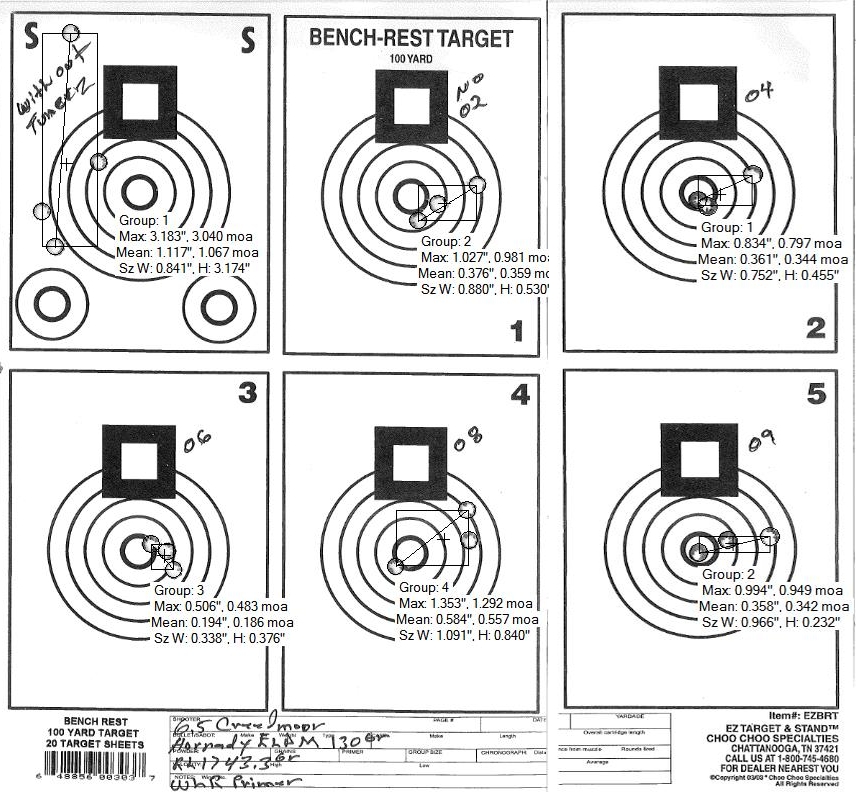

Darrell Jones handload data

Finally, I want to show the reader a few hand loaded groups done by a gentleman who was one of my consultants on this project, Darrell Jones, using the same model tuner. These represent a case where Darrell had a powder, bullet, and velocity he wanted to shoot but when these things were combined they were a terrible fit for the rifle. You can see that without the tuner it is just awful. The plan was to use the tuner to fix the mismatch between the rifle and the particular load he wanted. The improvement between the un-tuned load with it’s 3.2″ group and the tuner at setting 06 with a .5″ group is pretty dramatic.

Conclusion

Harmonics is often cited as the biggest factor in internal ballistics effecting group sizes by competitive shooters. While this might feel like the truth to a competitive shooter who handloads, I now suspect the truth might me more accurately stated that Harmonics was the last major factor to be effectively controlled by competitive shooters. Until tuners (1994) and high temperature stability powders (1996), harmonics was a devil to get a handle on. Of course, before that competitive handloaders had already tackled problems like consistency in neck tension, seating depth, and charge weight not to mention more esoteric things like neck turning, case volume measurement, flash hole deburring, weight sorting, and primer pocket uniforming. When you already have a very, very, consistent ammunition harmonics looms large in the equation.

Factory ammo, while much better than it used to be, and really pretty impressive, is apparently still a very long way from handloads in consistency. I suspect that factory ammo, being tested and optimized for performance in a variety of different guns, may also be a bit less harmonically active. The net result of this is that you are unlikely to see noticeable improvement in a factory load by tuning it. The best course of action for a factory ammo user is still to try out a variety of different quality rounds in your rifle to determine what it has a taste for instead or trying to tune for the one you wish it would like best.

Acknowledgements

In addition to the information made available by the three gentlemen mentioned in the background section, I spoke to several other industry experts in the course of writing this article. Their expertise was invaluable. Thanks to Darrell Jones for letting me pick your brain about tuning procedure and what to expect. Also thanks to legendary .22lr smith Gene Davis and custom rifle smith and tuner manufacturer Mike Ezell of Ezell Custom rifles for your insights. Lastly several companies and individuals helped in putting this article together by providing some of the products used. Thanks to Walter Harrell of Harrell’s Precision for the information he provided as well as the tuner. Thank you to Capstone Precision group for providing the Lapua ammo and Ruag Ammotech for providing the Norma ammo. I appreciate your being willing to effectively provide funding in kind toward adding to the knowledge base of the shooting sports. Furthermore, it is a show of confidence for a company to be willing to put their product out there to be used by a publication in which they will not have editorial control. Believe me when I say many are not so interested in press over which they do not have control.