I see a lot of questions regarding the wind posted on the internet, and many of the answers are rooted in history, not in modern principles. The old school mantra of, “If you want to learn how to shoot in the wind, grab a case of ammo and shoot in the wind,” is outdated. This mindset is considered incorrect because, without a starting point, you’ll hunt and peck, struggling precisely like the day before. You need a plan; you need a foundation in the wind to understand what you are doing.

Sometimes repeating the same information in a different way resonates with a new group of shooters.

Over the years, we have learned to manage the wind much more efficiently. The model to dope the wind we use goes back in time; it’s revisiting the math instead of using arbitrary numbers or values. Shooting is the longest-running game of telephone, so information has been reduced to shortcuts or pared down, so it only works in limited situations. Returning to the original thinking, we can understand the wind quicker and more comprehensively. There is a plan; we have a method for educating the shooter.

Breaking down the Big Picture

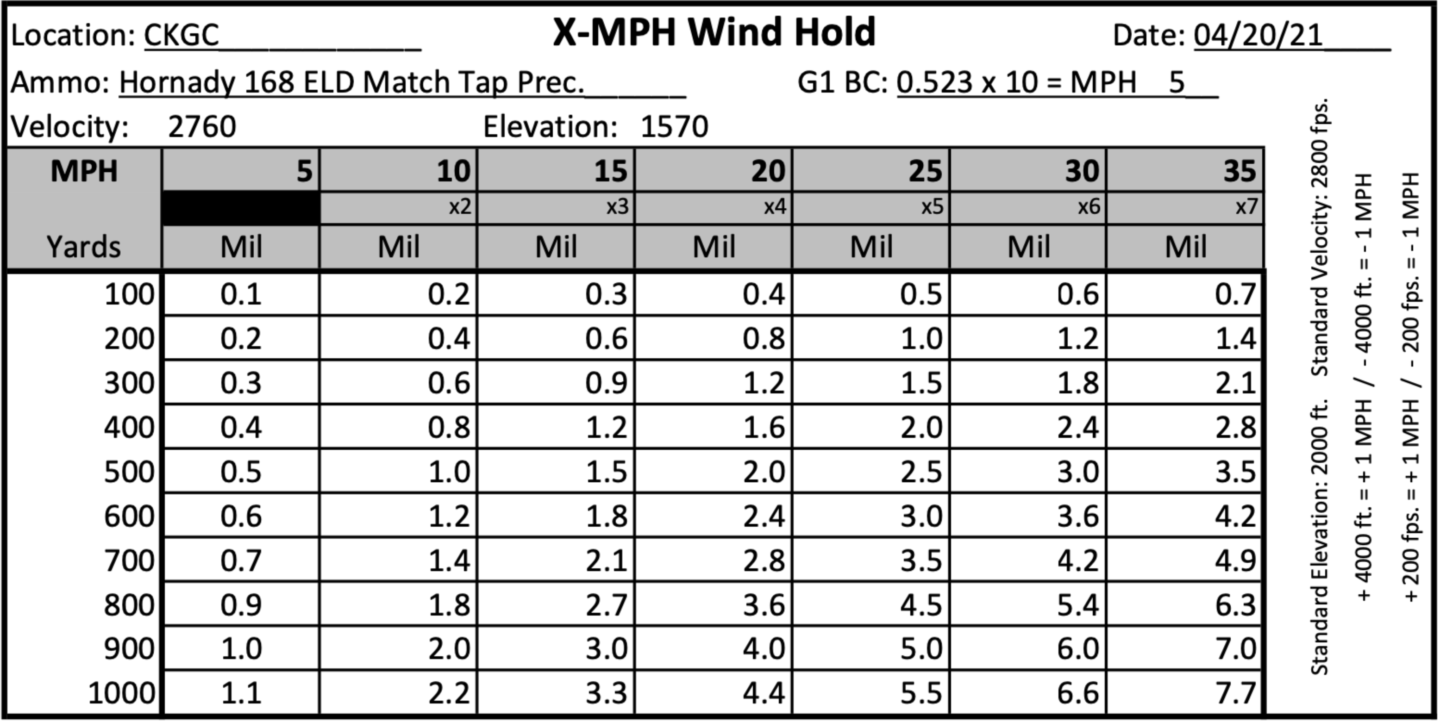

To begin, we want to look at the individual out there. We see a wide variety of calibers being used today. Every caliber manages the wind differently, so how do we cut to the chase to understand our bullet’s characteristics in the wind. Very easy, the first number of the G1 B.C. is our answer. Today, everyone talks about G7 B.C.s and using those numbers vs. G1. There is a fundamental reason we used G1 for 80 plus years when you consider the shooting world modeled G7 in 1940. They were well aware of the G7 Drag model but used G1 because it included a wind component.

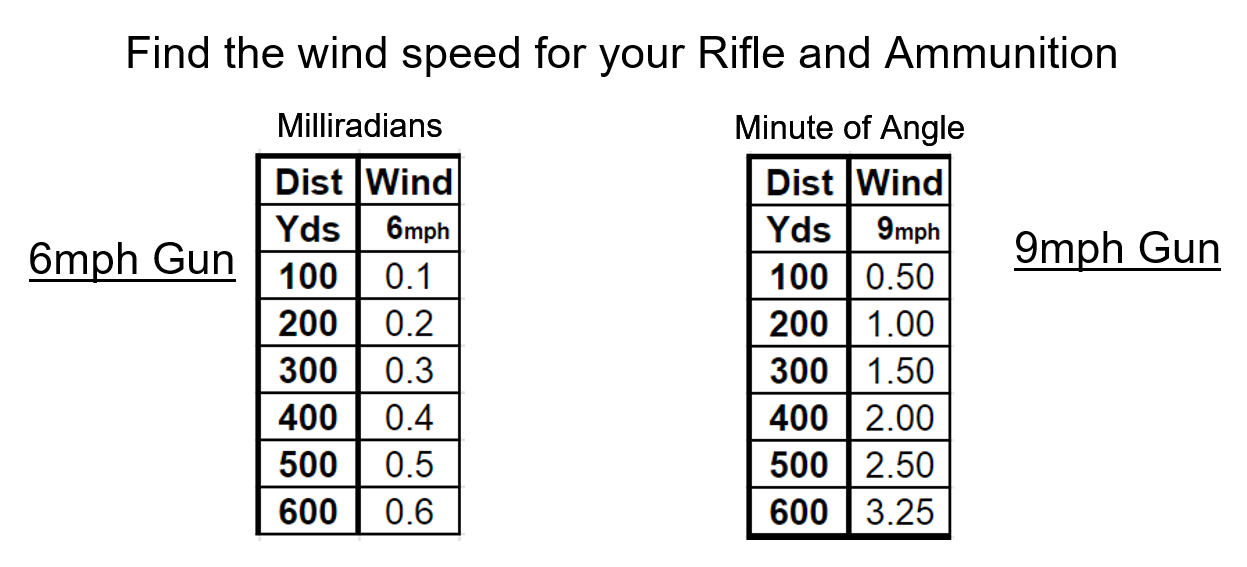

Before we break down the wind component of the B.C. numbers, understand something equally important. We moved away from this model because we shot M.O.A. Style sights and scopes for many years. The numbers using M.O.A. change the wind value to 10 M.P.H. This speed is where the game of telephone comes into play; we just defaulted to using a 10MPH value because that matched a 308. They cut out the long hand math part and just gave you a 10MPH value assuming you had a 308 in your hand. Today with Mils, we can see the flow of the wind calls much better.

M.O.A. Sidebar

If you are interested in M.O.A. wind calls, you want to use the British method, although today, with modern bullets, the value is 9 M.P.H., not Ten. At 10 M.P.H., you have 1 M.O.A. per 100-yard line adjustment using the British Method. I will not dive into M.O.A. as it’s nowhere near as intuitive. We are moving away from M.O.A. scopes in precision rifle shooting beyond the paper target disciplines. Those targets are calibrated in M.O.A., so it’s understandable why they use it.

For example, using ten mph as our base wind, you use the following shortcut.

British Method Math

Range 600, velocity 2-3mph =1.5 MOA

Range 600, velocity 5 mph = 3 MOA

Range 600, velocity 10mph = 6 MOA

Range 600, velocity 20 mph = 12 MOA

These numbers are all I have for the M.O.A. crowd.

B.C. Method for Mil Based Shooters

Looking at your ammo box, find the G1 number for the bullet being used. That first number is the wind speed for your rifle. Understanding right off the bat that B.C.s are muzzle velocity-dependent, if your rifle is on the fringes, as with a short barrel or extremely long one, it will not line up 100%.

This value is our primary M.P.H. Gun number. It’s our starting point until the rifle is doped and mapped out. Once we dope our rifle, we can use software to fine-tune our wind number, which we explained below.

You want to speak in M.P.H., not in the individual’s wind call. My wind call will not work if I shoot a 6CM and someone next to me has a 6.5CM. I have to give you the wind speed, not my personal correction. So in this context, we want to talk M.P.H.

We fine-tune the M.P.H. gun number by using software and setting the target range to 600 yards. I then scroll the wind speed until the pure wind value (Do not include the drifts) reads .6 Mils at 600 yards. We want the wind speed to match .1 Mils per 100 yards.

Speak in Miles Per Hour

Once this value is determined, we want to speak in only that value. Our rifle is a 6 M.P.H. Gun; we want to talk in 6MPH, 12MPH, 18MPH values. These brackets become essential down the road.

If you go on Sniper’s Hide or are already reading this, you can find charts and worksheets for the wind. Jackmaster on the site has offered up a host of resources.

We put this plan into practice on my private range in Colorado every month. We have to call the wind better than most because we could not survive, let alone host a precision rifle class if we didn’t. Our wind averages around 12MPH on any given weekend. We have worked with winds as high as 45 M.P.H. without stopping the class. We embrace the wind, especially when it grows to speeds beyond 12MPH.

As the bullet slows down, the B.C. changes; for a 308, this change might happen between 600 and 700 yards. For other calibers, it might happen later in the bullet’s flight. Recognizing this fact, we move the gun speed down, between 200 and 800 we have a 6 M.P.H. gun, at 900 to 1000 we have a 5 M.P.H. gun and after it drops to 4 M.P.H. This adjustment helps us manage the flight path and the changes in bullet speed.

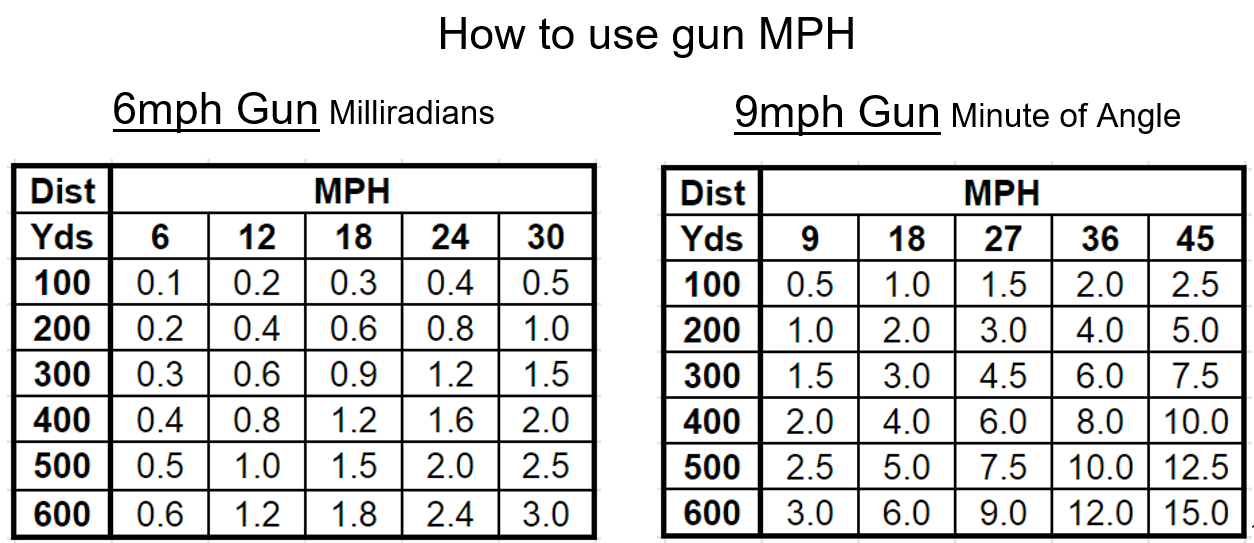

Cosine of the Wind Angle

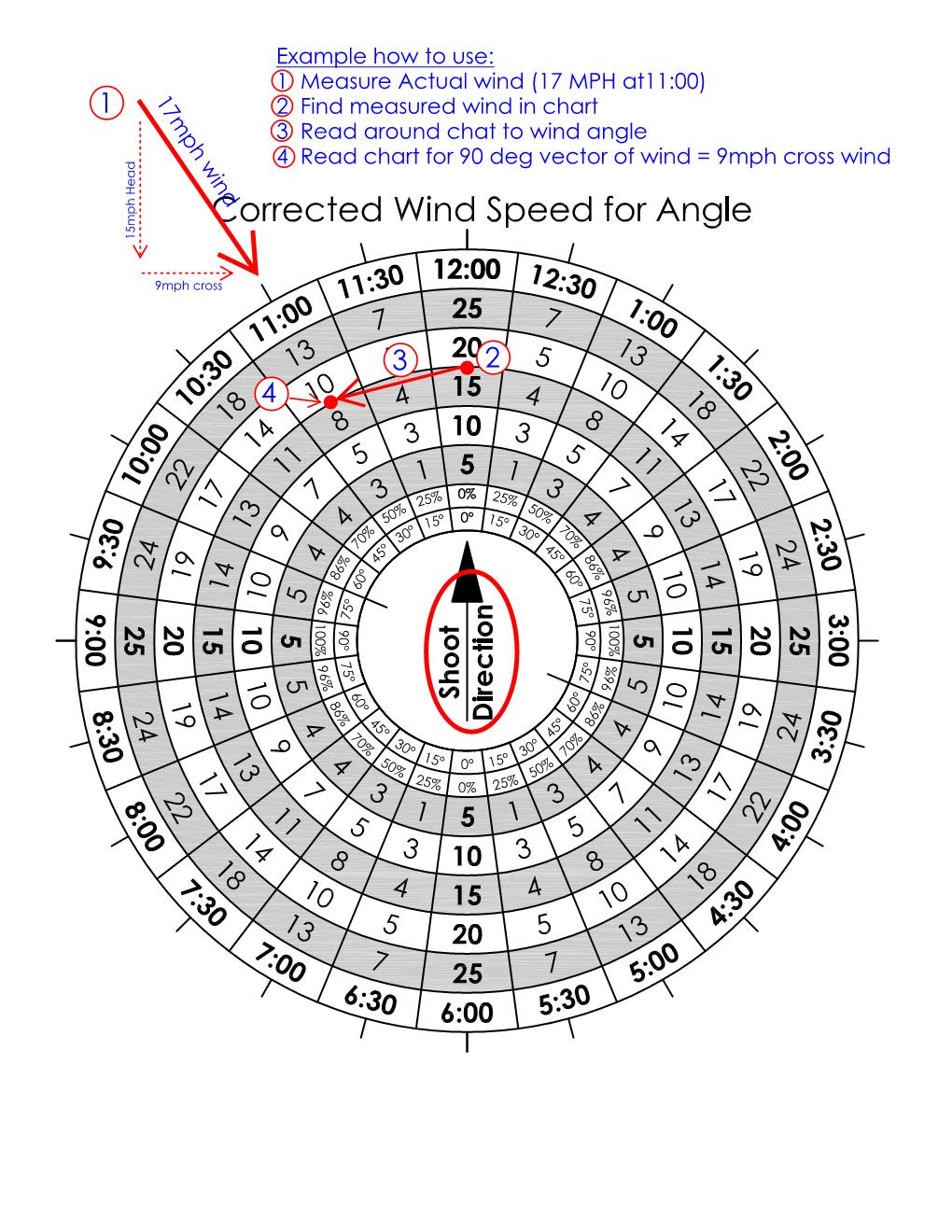

After we have determined the wind speed and applied that to our M.P.H. Gun Formulas, we have to look at the wind angle. Most people underestimate the wind because of the terminology surrounding the clock system. Most use the clock system versus degrees, but at the same time, the clock system has created a problem over the years.

You heard that experienced shooter proclaim the wind is at a 1/2 value. So the junior shooter assumes that is 1/2 the wind speed. Unfortunately, it’s not 1/2 the value but 1/2 the distance between 12:00 and 3:00. A 1/2 value 10MPH wind is not 5 M.P.H.; it’s 7MPH. Misunderstanding the cosine value is a common mistake.

We have an excellent cosine chart on Sniper’s Hide to help you determine the actual value of the wind. Using the clock is excellent; understand the values and not follow the terminology. Remember, a 1/4 value wind is 50%, not 25.

Determining the Wind Speed using a Meter

I don’t subscribe to the models who talk about grass, leaves, and trees. We don’t always have those indicators, and different materials have different characteristics. We have next to no indicators on my range, so we must use a meter.

Let’s talk using a Kestrel to dope the wind. The Kestrel is my preferred tool for doping the wind. I love the device in a lot of ways. We can read the wind to better than 1 M.P.H. at my location. I can “true” the wind the same as do my elevation to give me a great starting point for my calls. There is a lot I use the Kestrel for, atmospheric conditions, wind speed, ballistic solutions.

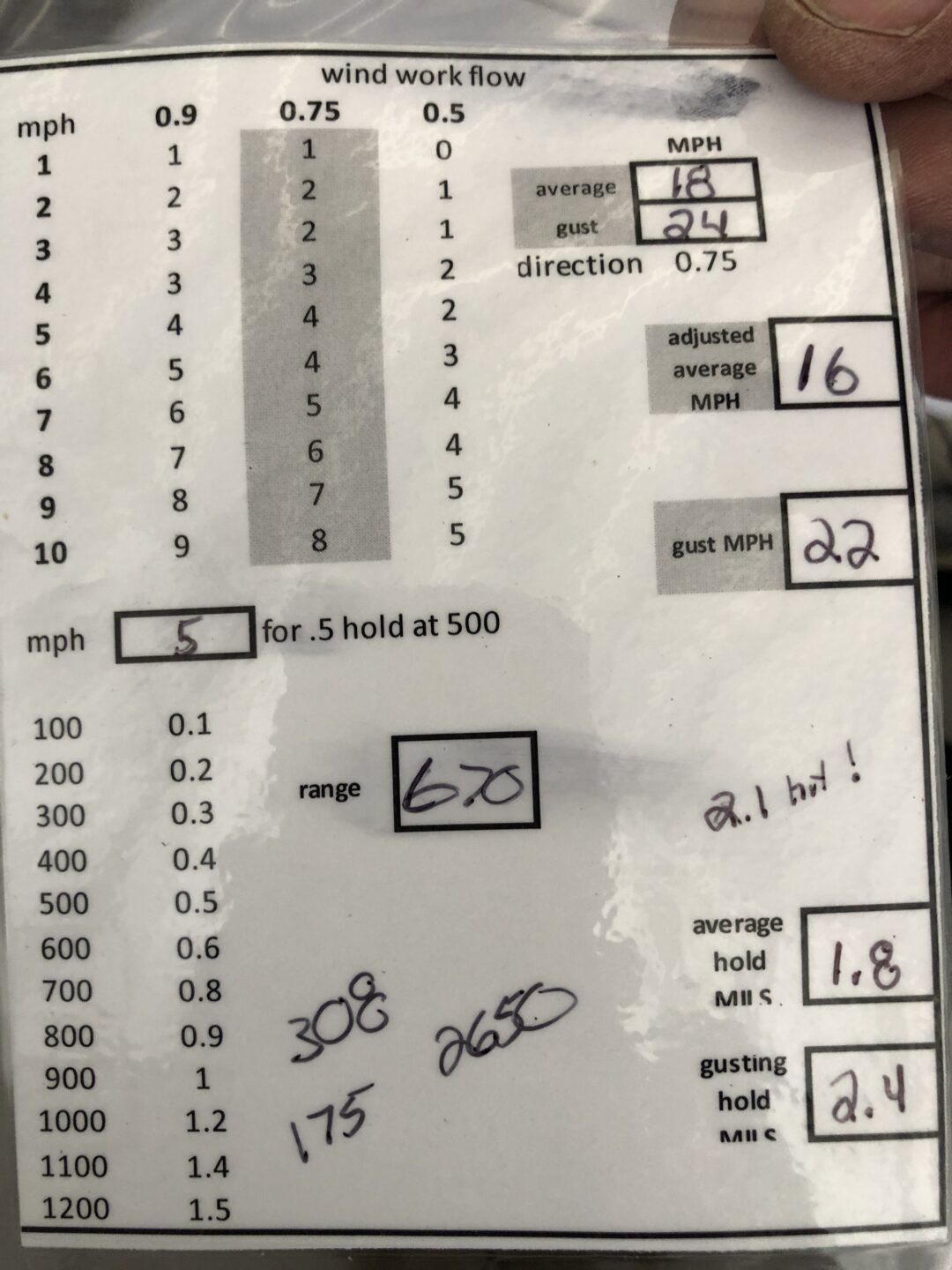

First, the shooter wants to determine the direction; the lanyard is fantastic for demonstrating the wind direction. Point the Kestrel into the wind and let the lanyard help. Next, we want to read the wind for at least 1 Minute; 2 Minutes is better, but monitor the Highs, Lows, and Average speed.

I want to put a Mil value on the speed. I want to see how the wind ebbs and flows. Most software looks at the wind in a straight line. It assumes you have one value moving from 1000 yards to the shooter in the shape of a wall. The reality is more like the beach, wind ebbs and flows like the waves on the ocean. It’s constantly changing.

Be Bold !

Now don’t get paralyzed thinking you can never manage the changes. You have to be realistic in your expectations, but you can manage the changes successfully by determining these values and understanding your conditions.

The values recorded help us create a plan, we need to know what the wind is doing, and now that I have an initial reading, I can dope my rifle for the wind conditions.

Wind Zones

We talk a lot about the wind zones and their various effects determined by where and how the wind hits the bullet.

I have reduced my wind zone discussion to just wind at the shooter. Yes, I recognize we have Mid Range Wind and Wind at the Target, but as a newer shooter, focus on you. The more experience you get, the further downrange your readings will be valid, but in the beginning, look at wind at the shooter.

It’s interesting how different shooting disciplines look at the wind; Square Range shooters do wind Mid Range; others try to focus downrange at the target, but at the shooter is the foundation for all calls. Rarely is the wind being blocked at the shooter, yes it happens, but I am not talking about the fringes but more so in general terms. I dope the wind at me and then use the downrange conditions to adjust my calls when I am in the scope.

Each location has their pro and cons, but generally speaking, I focus on the wind at my location. I will attempt to value downrange conditions and changes, but it’s more about the meter in my hand. First, you estimate the speed; next, you validate the conditions with a meter. This method builds your personal database by applying a value to the observed conditions.

I break the wind-down two ways: the science and the art departments. The science department is my wind meter; the art department is everything else because it is an artistic interpretation of what I am feeling, seeing, and hearing. My Kestrel matches my observations to an actual value.

Practical Application

How do we apply this M.P.H. gun method to our shooting? Do we hold or dial the wind? What are we doing behind the rifle?

The Sniper’s Hide Shot Process is W.T.F. this is my mantra.

Wind, Target, Fundamentals, I dope the wind first, always looking at their conditions as it’s my wildcard. Do I hold or dial? I am mostly holding the wind because it changes so often, and I don’t want to break contact to dial. But in certain situations, I will dial; I am not opposed to dialing on some wind to keep me in the center of the reticle.

If the wind is 8 M.P.H. and I am shooting at 600 yards, that means I am using .8 for my initial wind hold. Why .8, well, a 6 M.P.H. gun will move the strike .6 Mils at 600 yards, so adding 2 M.P.H. over that value, I get .8 if the wind was 12M.P.H. that puts me in my second bracket so that the wind call would be 1.2 Mils.

I am measuring the speed, applying that to my target range, and sticking to my plan; we strive to observe any hits or misses using the fundamentals. This method allows me to correct on the fly. I can believe the bullet based on my observations through the scope. We are reading, not writing; I see it and adjust.

Wind management is accomplished on the fly without a calculator. If you are doing longhand math in the field, you have already lost the fight. The numbers are small enough to do in your head. .6 x2 = 1.2.

Working in Brackets

Lastly, I want to talk about wind brackets. As noted above, wind ebbs and flows; it does not move in a straight line. Often we see wind gusts that can be larger than the target or smaller than the target. By noting the size of the target upfront, we look at using brackets.

Wind brackets use more than one value on the plate. We have an average estimate for the wind call of .6 Mils and a gusting value of .8, so the goal would be to place both on the target simultaneously.

We flash mil the size of the target and then overlay the brackets as needed. Not every target can have two wind calls on the plate, but it’s a great way to manage the wind quickly. In competition, it’s better to hedge your bets versus depending on a single value to get the job done. Shooters will say that the wind is between 6 M.P.H. and 8 M.P.H., so using both those numbers on the target increases our chance of a hit.

No Voodoo

You need a starting point; just saying shooting in the wind will yield results is foolish. We don’t want to waste ammo; we want a proper training program to learn. It’s cause and effect; it’s math, and the math lines up as wind drift has a value, not voodoo.

The curtain is being pulled back on the mystery we call the wind every single day. The more situations we shoot in, the more we understand what the wind is doing. We recognize anomalies, like terrain impacting the wind’s speed and movement. Terrain creates issues like dropping obstacles in a stream, turbulence happens, and wind being invisible means we don’t see those changes. Most of those changes are localized vs. the big picture, which is why we see flags moving in opposite directions. In that case, try to get in between terrain; it might be a tree line causing a backflow, so line up in the middle away from the edges.

Don’t be afraid of the wind; embrace it. When the speed climbs, grab your rifle and work within the brackets, I promise the numbers will work. Remember, this is the beginning of the journey, not the end or even the middle.