Last year I did a review of the TriggerTech single stage 700 platform triggers. Originally, I had planned to write an addendum to that review after seeing the two-stage triggers announced at SHOTShow of that year (2019). That was before I got a look inside the two-stage design to analyze how it works or had the opportunity to meaningfully test one. Now that I have done so, it is pretty clear to me that the two-stage needs its own review because it is not so much an alteration of the single stage design as an entirely new trigger.

Table of Contents:

-What is a Two-Stage vs. a Single-Stage Trigger

-Core TriggerTech Elements

-How TriggerTech’s Two-Stage Differs from their Single-Stage

-Analysis of the Two-Stage’s Release Sequence

-Testing the TriggerTech Two-Stage 700 Triggers

-Summary and Conclusion

What is a Two-Stage vs. a Single-Stage Trigger

Before I go into the unique design elements of the TriggerTech two-stage, I should probably explain the general difference between two-stage and single-stage triggers, as many shooters do not have experience with two-stages and therefore do not understand the difference.

We should start with how a single-stage trigger is supposed to feel in a precision rifle. Ideally, on a single stage, you have no perceptible movement before the trigger breaks. If the trigger moves some loosely before you feel any spring force pulling against you and before you have any sear movement, you call that slack. If you feel a gritty movement as the sear perceptibly moves before releasing, you call that creep. You don’t want either of these on a precision rifle. You just want the trigger to not move in any perceptible way until the break, and that is exactly how the best single-stage triggers feel.

Of course, if you have a single-stage trigger set really light, like say 4oz, it can be pretty easy to accidentally set it off as you move your hand into position, as the act of simply finding the trigger with your finger is likely to bump it hard enough to set it off. On the other end of the pull weight spectrum, it can also be hard to tell exactly when the trigger is about to break on a heavy pull, as everything between 3 and 4 lbs might feel more or less the same to the shooter, making it pretty hard to time the shot release and pretty tempting to yank instead of squeezing the trigger. Using a two-stage can substantially mitigate both of these issues.

The ideal two-stage pull has a first stage where there is smooth trigger movement and a consistent amount of spring force. During this stage the sear is typically not moving and the trigger is usually just pulling against a spring not in contact with the rest of the mechanism, including the sear etc. At the end of the first-stage’s movement, the trigger movement stops on the second stage, which is known as ‘the wall’. Here, as on a single-stage, there should be no more perceptible movement until the trigger breaks.

The benefits of this two-stage movement pattern are several. First, an inadvertent bump on a light trigger is less likely to set it off since it takes substantial movement to reach the second stage, even if it is a light-two stage and that movement doesn’t take much force. This makes it easier to marry up to a light trigger without setting it off. Second, you can make a heavier safer trigger feel lighter by going with a fairly heavy first stage and a bit lighter second stage. This is because you perceive changes in the force you apply more than the absolute force. A 16oz first stage followed by an 8oz second stage feels more like an 8oz trigger than a 1.5lb trigger because you perceive the difference in pull force between the first and second stages more than the combined weight of the stages. That is a big deal and, frankly, it feels a little like cheating physics. A 1.5lb trigger takes a good bit of concentration to break well in a single-stage, but is pretty low on the mental overhead when it comes to breaking it cleanly and on time when it feels more like an 8oz on a two-stage. Lastly, two-stage designs, with their intrinsic movement, offer designers the opportunity to make the trigger even more intrinsically safe by putting in place passive internal safeties based on that movement. Not all makers do this, but it is possible. For my part, in the couple of years that I have been playing around with two-stages, I have come to see the concept as a large advantage in trigger control and I pretty clearly prefer them now.

Core TriggerTech Elements

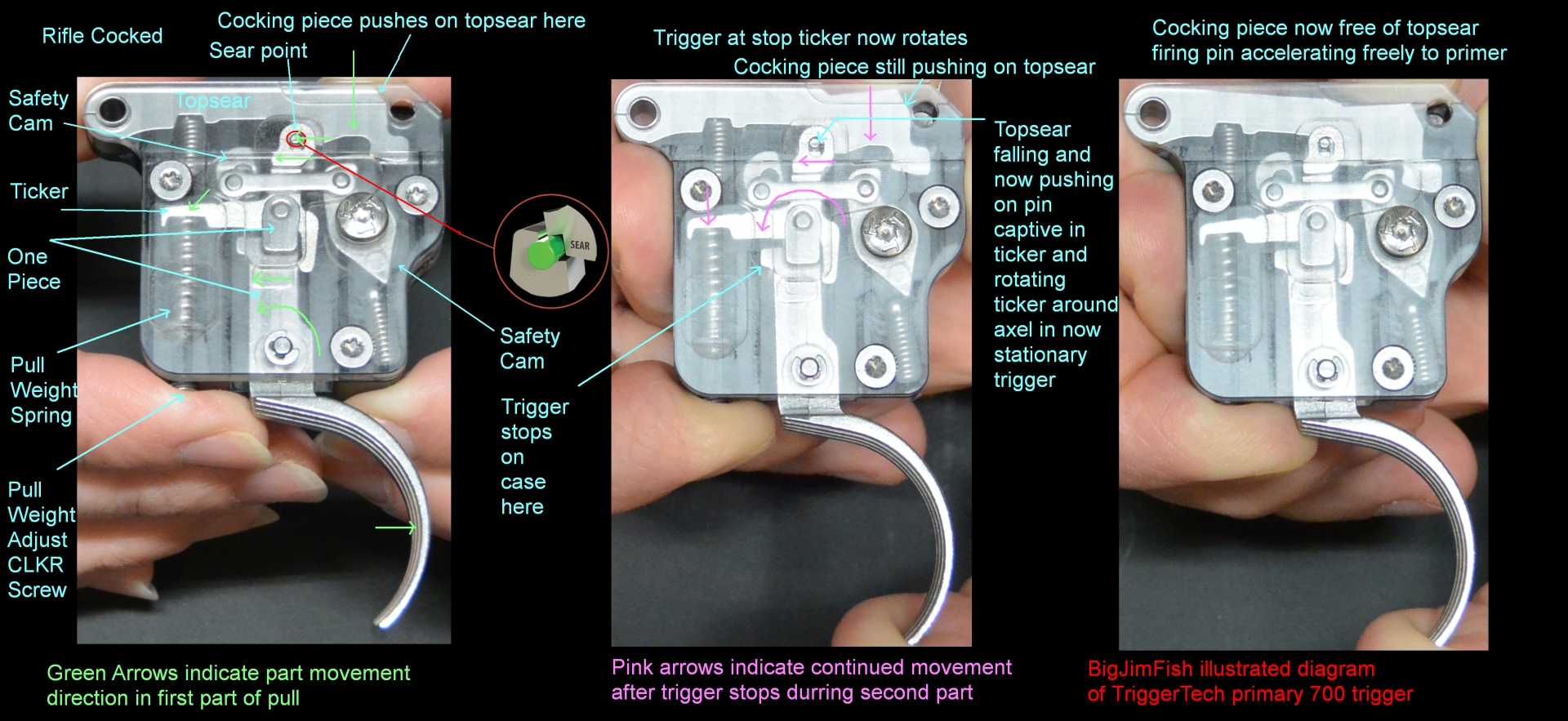

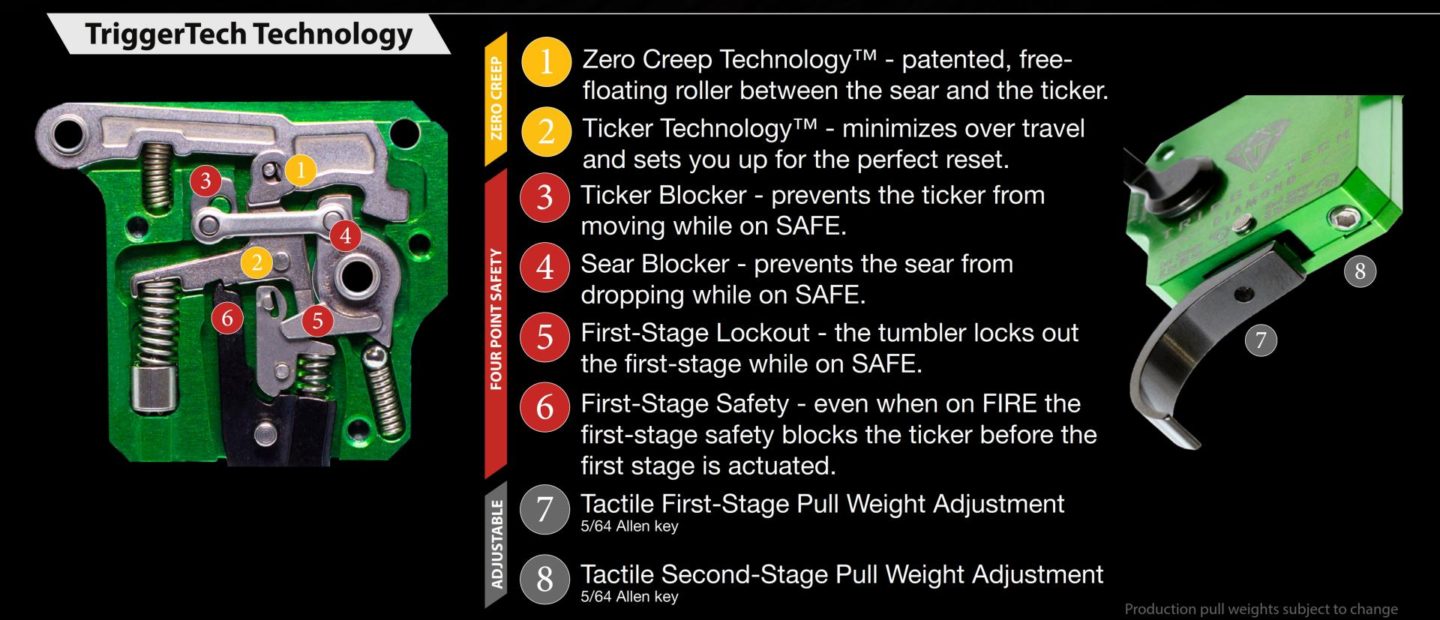

Although the TriggerTech two-stage 700 triggers are an entirely new and of a different design than the single-stage triggers, they do share some TriggerTech core technologies. Both the single-stage and two-stage triggers feature FRT, TKR, and CLKR technologies. The CLKR just means that they have put clicks in the pull weight adjustment screw. TriggerTech must have felt they needed to name, and then acronym, clicks in the pull weight screw to add to their ABS (acronym badass score). It is a good system, though. It both allows you some idea of how much pull weight adjustment you are adding or subtracting and also keeps the pull weight adjustment screw from working itself loose. The TKR refers to TriggerTech’s overtravel stop system, or at least that is what they call it. In reality, the TKR is a lot more than this and a little less at the same time. The trigger actually stops against the case wall and not the TKR, so it isn’t really an overtravel stop. At that point, when the trigger stops on the case wall, the TKR is in motion and actually continues to move after the trigger stops. This ability for the TKR to keep moving lessens the overall travel necessary for the trigger. This is a concern when adding a roller to the sear mechanism, especially when you intend that roller to have a significant distance to move (the equivalent of sear engagement) before the topsear falls for safety reasons. This brings us to the biggest tech difference, the one that really put TriggerTech on the map: the FRT or Frictionless Release Technology. In simplest terms, FRT is a roller that is interposed between the two sear surfaces to replace the sliding friction with much lower rolling resistance. Doing this basically allows for much greater sear engagement without the feeling of creep that is introduced on a conventional trigger design with greater engagement. To get a conventional trigger to the point that you don’t feel creep, you must make the sear engagement so small that you can’t get perceivable movement of the trigger without it breaking. In other words, you have to get the sear balanced on a knife’s edge because any movement not resulting in the trigger breaking will feel gritty and creepy. Because of the roller, movement on a TriggerTech instead feels smooth, so it doesn’t need to have minimal sear engagement to eliminate creep. Outside of the gun, you can feel a little of this smooth movement and some of the sear engagement the TriggerTech has working the trigger in your hand. Inside the gun, you can’t really perceive this, as the force the firing pin puts on the topsear is much greater than that of your finger when you are fiddling with the trigger outside of the gun. Inside the gun, all you feel is that the trigger falls away from your trigger finger more when the shot breaks than with conventional sear trigger. This gives TriggerTechs a unique feel during the shot break. The FRT roller is also the source of TriggerTechs legendary reliability and tolerance of dirt. Part of this is that it doesn’t have a sear balanced on a knife’s edge having issues when a little grit gets on that edge and part of it is the roller sort of brushing off dirt that gets on the sear surfaces as it functions.

How TriggerTech’s Two-Stage Differs from their Single-Stage

Despite all the unique TriggerTech technology added, their single-stage trigger is very geometrically similar to the very simple original Walker 700 trigger in that they are both one lever designs. In both triggers, that lever is even about the same length and in the same position. Therefore, the massively lighter weights you can get in the TriggerTech single-stage Diamond are the result of a combination of a rolling sear, differing pull spring force and geometry, and sear surface angles, rather than anything to do with mechanical advantage. It is rather impressive that they managed to accomplish such pull weights in this way and it clearly took some pretty tight tolerances.

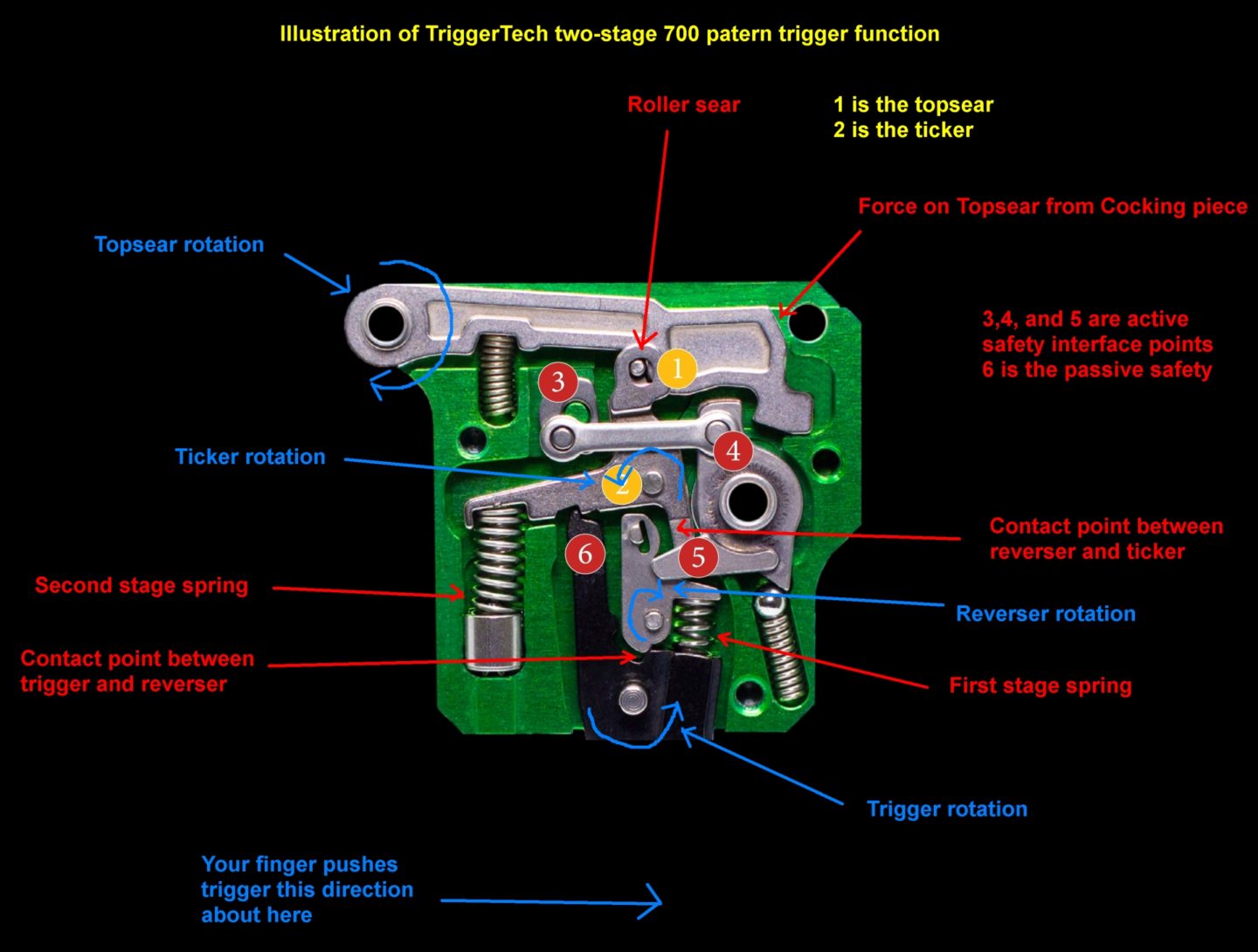

The two-stage departs from the single lever design in favor of a three lever design. Multiple levers are integral to how most lightweight match triggers function since they allow for some mechanical advantage within the limited space allotted for a 700’s trigger housing. Of course, with more levers there are more moving parts and so TriggerTech also added a few more safety blocking points. The single stage had two safety cams. One blocked the topsear and the other, the TKR and trigger. Their two-stage adds a second arm to the first cam so that it now blocks both the topsear and the reverse lever (which in turn blocks the trigger). The second safety cam now blocks just the TKR. Additionally, the trigger in the two-stage now has a passive safety on it which blocks the TKR until the first stage is pulled. This passive safety is particularly helpful in reducing slam fire conditions when using out of spec actions at low pull weight settings.

Analysis of the Two-Stage’s Release Sequence

TriggerTech’s single-stage trigger’s release was already pretty complicated and the two-stage is more complicated still. Since users are not supposed to disassemble or take the cover off their TriggerTech triggers because the way they are assembled renders them not likely to be reassembled correctly, I will explain and provide illustrations. With the rifle muzzle pointed left as in the diagram below, here is how it goes:

As you begin pulling, the trigger rotates counter-clockwise pushing against the bottom of the reverser causing it to rotate clockwise. The first stage pull spring is between these two parts and is compressed from both sides by both parts. Near the end of this first stage, the passive safety at the end of the top of the trigger piece will clear the notch of the TKR so that that piece is no longer blocked. The first stage will end when the clockwise rotating reverser touches the lower arm of the TKR. The user will feel the reverser coming to a stop on the TKR as the wall. As the user continues to pull the trigger, the TKR will rotate counter-clockwise compressing the second stage spring and moving the roller forward between the TKR and topsear. When the roller gets far enough forward (not very far at all) it will clear an edge on the topsear. This is the point at which the shooter will perceive the trigger to have broken. Having cleared the edge on the topsear, the roller will be pushed rapidly forward by the topsear. This in turn rotates the TKR further forward so that the topsear can fully clear the rifle’s cocking piece and fly forward with firing pin in tow. The shooter does not perceive this motion, however, as the trigger stops on the case front soon after the roller clears the edge on the topsear.

Testing the TriggerTech Two-Stage 700 Triggers

For this review, TriggerTech sent me both a Special and a Diamond. Because the production springs were not yet present, my examples had hand-modified springs, though all other parts were production. As such, you can expect some variance between the minimum pull weights I recorded and what you will. In my triggers, the Diamond had a min first stage weight of 2.1oz and min second stage weight of 4.9oz. The Special had a min first stage weight of 4.76oz and a min second stage weight of 5.82oz. In the case of the Diamond, this meant the first stage went lower than advertised (2.1 vs. 4oz) and the second not quite as low (4.9 vs. 4oz). For the Special, both stages went well below advertised (4.76 vs. 8oz and 5.82 vs. 8oz) and were really not all that far from the Diamond’s advertised numbers. For those interested, the final piece of the puzzle delaying release of these was actually getting the springs right. I expect they will be upping the weight on the Special springs from the one I used as there was very little difference between the minimum weights in the examples I had, and yet, that was the only difference as far as I could tell. I understand from an interview the TT guys did that the geometry of some of the surfaces is a little different between the two models, but I don’t feel it. I eventually set both examples to 14oz total with the second stage set to min and the first stage to the remainder, and found them totally indistinguishable.

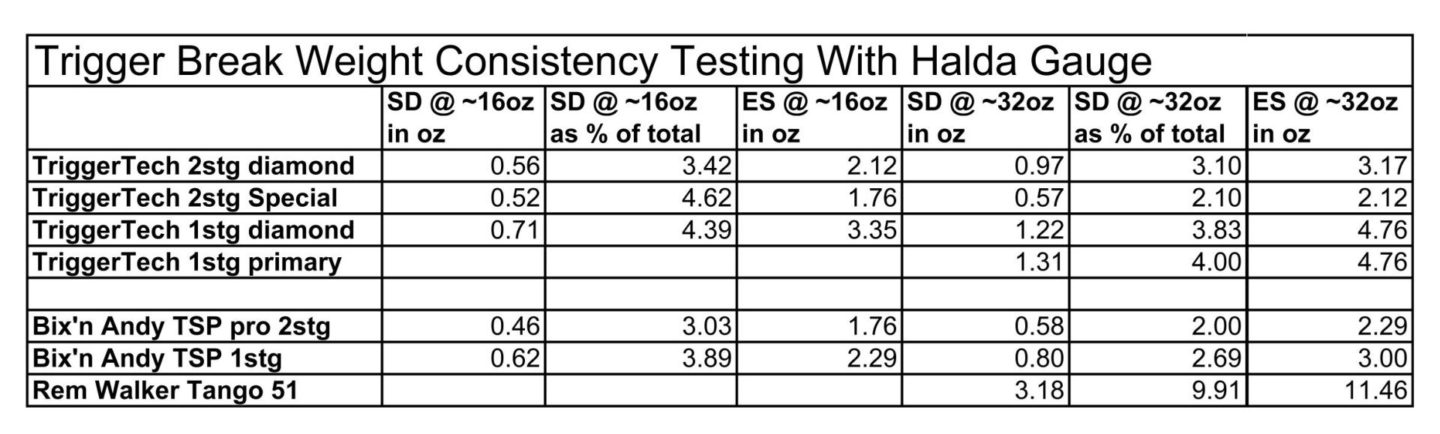

When I did the TriggerTech single-stage 700 trigger’s review, I was using borrowed Correx force gauges. Those have since been returned and I purchased a similar quality (very good) Halda force gauge to use going forward. You would not believe how inexpensive you can get a really good used force gauge. I would recommend this to my fellow shooters over one of the low quality gun brand options – if I thought there was really any reason for most shooters to have a trigger pull gauge. I certainly never did until I needed quantitative data for doing reviews. The range on my Halda is ~3.5oz to ~35oz with a little leeway to estimate on either end of the range as it is analog. Since, with a new gauge, I needed to take new data on all the triggers to be compared, I took the opportunity to refine my break weight consistency testing methodology. Most importantly, I decided to make more of an effort to test every trigger at specific, similar pull weights. Each trigger was therefore tested at ~16oz and ~32oz when possible. For the two-stages, pull weights between the stages were set as close to equal as possible at each test weight. The TriggerTechs were capable of being set equal at both pull weights, but the Bix only goes up to about 8oz on the second stage, so that was the setting for both its tests.

The two-stage TriggerTechs tested, on average, a little more consistently than the single-stages did. I’m not sure if that is the result of having two springs involved in sharing the load or perhaps being a three-lever instead of a single-lever design. In the case of extreme spread, the Special two-stage actually posted the best numbers overall if only by a hair (ok, probably less than the weight of a hair). Frankly, I thought the numbers on the single-stage TriggerTech’s trigger were fine, so, even better for these. In practice, I do not notice any weight difference in the break shot-to-shot and so do not have any difficulty having shots break when I intend them too.

This brings us to safety testing. I tested the TriggerTech two-stages for slam fires as well as drop safety in a variety of states in several different actions. I was not able to induce a slam fire or a discharge from dropping the rifle with the safety on. However, in some situations it was rather easy to induce a discharge by dropping the rifle without the safety on. At minimum pull weight for both stages, the two-stage Diamond would discharge when the rifle was dropped on the butt from four inches or higher. At 12oz pull weight (6oz each stage), it took about 12 inches of drop height onto the butt to discharge the Diamond. The Special would also drop fire on minimum weight though in its case, it took about a foot to set it off, presumably because it has a higher minimum pull weight. I spoke to TriggerTech about this and they have also found the butt down drop condition to be the most critical for this trigger. They have found that roughly 8oz of first stage weight or 16oz of total weight is necessary to render the trigger drop safe with even pretty aggressive slamming of the rifle on the butt. I was able to duplicate this. At 8oz first-stage and minimum second-stage weight, neither the Diamond nor Special would drop fire when bounced aggressively on the butt. I should mention here that most super light match triggers are not drop safe at minimum weight. The single stage Diamond was, however, and the one I tested actually went sub 3oz, so I was surprised and disappointed that the two-stage proved easy to set off in minimum condition, especially since when I initially analyzed the design I did not expect it. The origin of the susceptibility seems to be that the pad area of the trigger piece is heavier than the passive safety area on the other side and that a combination of bulking the top and slimming the bottom would reduce susceptibility, yielding probably the safest 700 trigger on the market.

After doing all the lab testing, I strapped each of the triggers in a rifle and started field testing. The first thing I noticed when actually shooting the triggers is how little I noticed the very short ~1/16″ first-stage travel. This is a much shorter first-stage travel distance than other two-stages I have used, and I was a bit worried that it just wouldn’t feel or work like a two-stage from a human operator standpoint. I typically run my two-stages with a heavier first stage and lighter second, and have found that they will basically feel to me like a trigger of just the second stage’s weight insofar as how much concentration is required to break them cleanly. So, if I have an 8oz first stage and 6oz second stage, the trigger feels to me as easy as a 6oz trigger even though it is just shy of a pound at 14oz. I thought that the very short first stage might be a bit of an issue with this, but it proved no obstacle at all. In fact, I did not find anything I disliked in shooting the two-stages. They felt smooth in the first stage and predictable and clean at the break. Absolutely excellent.

Summary and Conclusion

At the most basic level, both of the TriggerTech two-stages feel great. The have a smooth, consistent first stage; a solid, stationary, clearly distinguishable wall on the second stage; and a clean, creep-free break that is totally predictable and consistent. They feel textbook: what you are looking for in a two-stage and the shorter-than-average first stage travel I worried about sitting at my desk fiddling with them did not matter at all in practice. Running a high precision force gauge on these new two-stages also revealed some of the most consistent break weights I have tested, a step up from the consistency of TriggerTech’s single- stage, which was itself no slouch.

A look under the hood of these triggers reveals the most staggeringly complex design that I have ever encountered. They have a safety that actively blocks three points in the trigger mechanism; a second, passive safety; and all the complexity of TriggerTech’s TKR, CLKR, and FRT mechanisms plus a three-lever actuation mechanism all crammed into the small footprint of a 700 trigger. It is surprising that after all this they were lacking a little in drop-safe testing (when the first stage is set below 8oz or total trigger weight below 16oz) for the simplest of reasons, an imbalance in the mass of the trigger piece itself. This is not to say that most of its competitors are drop safe, some are not, but TriggerTech’s single-stage tested so for me and looking at the design of this two-stage, I expected it to be as well.

I am catching myself here digressing on fine points of design and ignoring obvious and tremendously important features. Just as with all TriggerTechs, the pull weights for each stage on these two-stage 700’s are entirely externally click adjustable with the trigger in the gun using the supplied hex wrench. The range of adjustment is massive, going from relatively low match type weights (8oz Diamond, 16oz Special) to quite substantial hunting type weights (44oz Diamond, 56oz Special). That is a 5.5x range on the Diamond and 3.5x on the Special. These ranges are also fully achievable without adjusting anything else on the trigger, swapping springs, or causing the trigger to become unsafe or non-functional. Even if you fully remove the non-captive second stage adjustment screw and lose it, the trigger will still function fine, though at its minimum pull weight. Lastly, TriggerTech’s roller interposed sear system provides not only a creep-free break but also the high degree of reliability and dirt tolerance that TriggerTech is probably best known for.