Not a vintage sniper rifle topic, but an interesting article on the 58-year old Ukrainian sniper who likely set a new wartime record. Domestic Ukrainian rifle with a US Bartlein barrel and a Japanese March-FX scope, looks like a 4-40x52 Genesis version. Ammunition was custom made in Ukraine. Article outlines use of ballistic software, incredible skill and clearly some incredible luck.

The Wall Street Journal, December 4, 2023

KYIV—The Ukrainian sniper had lain still for hours in near freezing temperatures when the command came to take the shot at a Russian soldier almost 2½ miles away. “You can,” his spotter said, and Vyacheslav Kovalskiy pulled his trigger.

The bullet took around nine seconds to reach its target, who doubled up and fell, according to a video of the shot reviewed by The Wall Street Journal. Kovalskiy and Ukraine say the shot set a new sniping distance record, breaking the previously acknowledged mark by more than 850 feet.

While combat hits such as this aren’t verified by a third-party adjudicator, the shot has offered Ukraine a morale boost when the country’s forces are struggling to make headway at the front line. A Ukrainian sniper, using a Ukrainian-made weapon and bullet, had broken the record. Sniping has played a prominent role in the war with Russia, where static front lines in a flat landscape suit the discipline, even as drones and mines change the way the marksmen operate.

Custom-made rounds used by Ukrainian snipers.

For conventional sniping, there are a lot of variables that are hard to quantify.

The macabre record was also a shot heard around the world of snipers, a group of highly skilled shooters who have long pushed the boundaries of just how far a bullet can travel with accuracy. Some are skeptical that Kovalskiy’s shot was a record.

To hit targets at ever-longer distances, snipers lean heavily on math, calculating a host of technical factors, from the air’s humidity to wind speed, temperature and the curvature of the earth. They also need a good rifle and a lot of luck.

On Nov. 18, Kovalskiy was already packing his rifle by the time the bullet reached its destination and a member of his team shouted that it was a hit. The shot was filmed and on reviewing the footage later, Kovalskiy and other snipers concluded it had been deadly.

“I was thinking that Russians would now know that is what Ukrainians are capable of,” Kovalskiy said, who hasn’t previously been named or spoken to the media.

“Let them sit at home and be afraid,” he added.

Several snipers and ballistics experts contacted by the Journal said that while the shot is possible with the equipment described, it would be hard to execute given the uncontrollable variables, not least the weather, that would have to be taken into account at such distances.

“For conventional sniping, there are so many variables that are hard to quantify, so the reality is anything over about 1,300 meters (about 4,265 feet) can be more luck than skill,” said Steve Walsh, a former U.S. Marines sniper instructor.

Kovalskiy’s shot hit around 12,470 feet, around a third longer than the Golden Gate Bridge. That distance would break a record of 11,600 feet set in 2017 by a member of the Canadian Special Forces in Iraq.

The 58-year-old former businessman’s journey to martial mythology started just before day break on Nov. 18, when he and his spotter, a partner who calculates distance, wind speed and other variables, set up positions across the river from a Russian military base in the Kherson region of east Ukraine.

The two men, who are part of a military counterintelligence division of the Security Service of Ukraine, or SBU, observed groups of Russian soldiers cutting wood. They considered these men’s ranks too low to shoot. At around noon, a group of five soldiers appeared and Kovalskiy noticed one instructing. He had his officer.

The spotter set to work. He used a laser to measure the distance to the soldiers. Using specialist software and meteorological data he concluded that there was a strong wind that would move the bullet around 200 feet from its trajectory. He calculated humidity and temperature, which affects how fast the bullet travels.

Even the spin and curvature of the earth has to be factored in for long-distance shots. By the time the bullet gets to its set distance, the target has already shifted with the earth’s rotation.

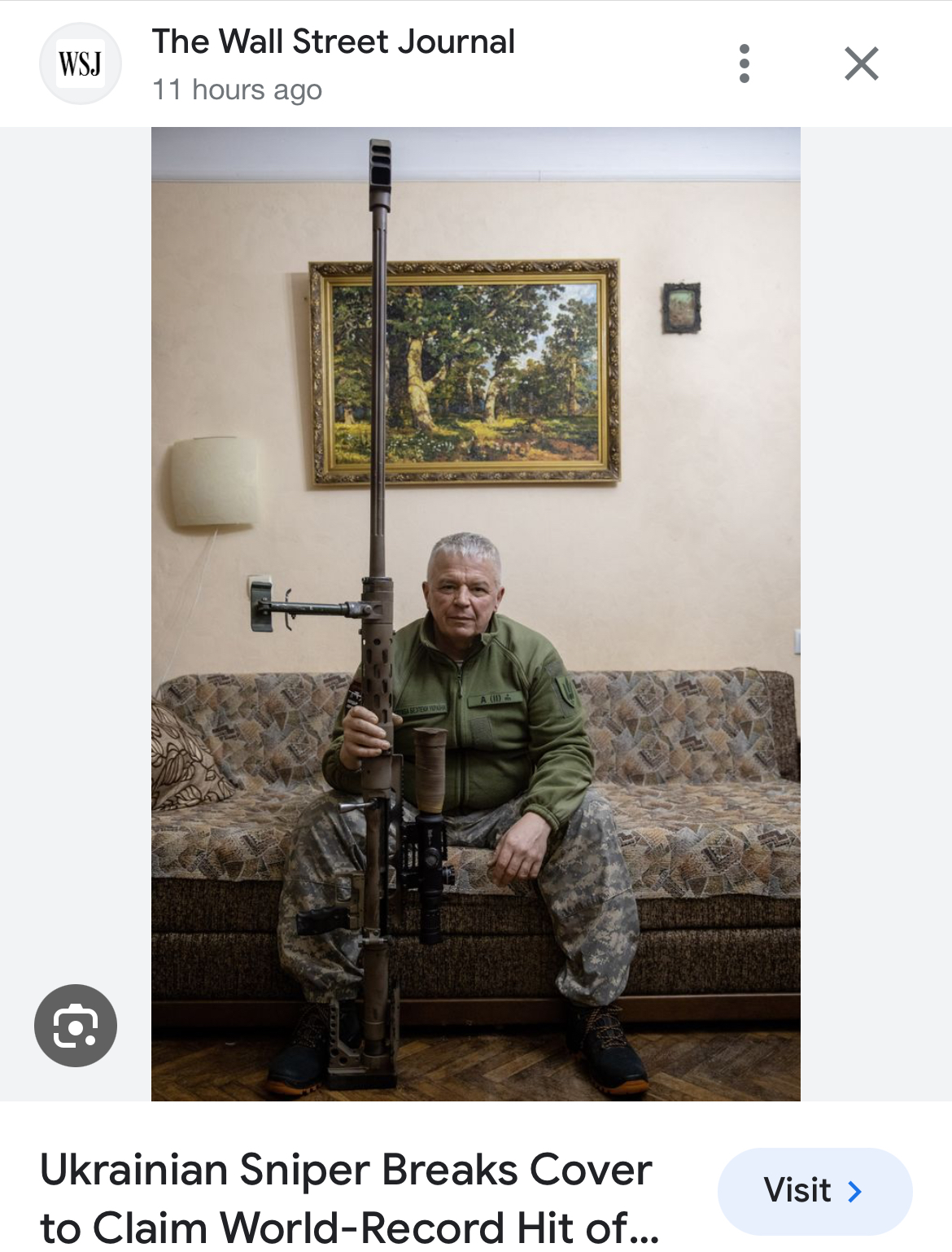

Ukrainian sniper Vyacheslav Kovalskiy packs up a custom made sniper rifle.

The scope on a Ukrainian sniper’s custom-made rifle.

Using all these variables, Kovalskiy tested a shot around 1,000 feet to the side of the target. It was a miss, the spotter told him.

They had got the wind speed wrong.

He quickly reset, reloaded and aimed.

“You have to (shoot) immediately because the wind changes constantly,” Kovalskiy said.

In video of the shot, the Russian officer can be seen gesticulating to men who had gathered around him. The spotter gave his usual command that he should fire.

“You can,” he said.

Kovalskiy pulled his trigger. The video shows a gap from shot to impact of around nine seconds, a period long enough that a target can have moved. U.S. ballistics expert Brad Millard timed the shot in footage and said that it was the correct time that this sort of bullet would take to hit 12,470 feet.

A sniper will aim their barrel above a target because gravity forces the bullet down. Kovalskiy’s shot was like a mini artillery shell, traveling over 330 feet above the level of the target before descending toward the unaware officer.

In the footage, the officer doubles up and falls and his men flee. The video ends.

The shot has been widely covered by Ukrainian news websites. It was also noted with pride by Ukrainian soldiers on the front line. In the Kreminna Forest in east Ukraine, a former sniper turned artilleryman said hearing the news was a “punch the air” moment.

“Everyone was talking about it,” he said.

Vyacheslav Kovalskiy holds a typical sniper round and a larger handmade custom round that he and his spotter used to shoot at a Russian soldier.

Ukraine needs a boost. A much-heralded counteroffensive has been stymied by stubborn Russian defense. The country has lost tens of thousands of soldiers and Russia continues to bomb civilian sites.

Countries in war often turn to combat legends to build morale, and countries in the former Soviet Union have a history of elevating the sniper to hero status. At the start of this war, Ukrainians traded stories of the “Ghost of Kyiv,” a Ukrainian jet-fighter pilot credited with shooting down several Russian planes. The Ukrainian military later said that rather than an individual pilot, the “Ghost of Kyiv” was meant as a composite symbolizing the combined heroism of its pilots.

Millard, the U.S. expert who designs software to test gun ballistics, says he doubts how the Ukrainian sniper team knows for sure that the officer was killed.

The shot hit its target in the chest or stomach area, Kovalskiy said. Having seen footage many times, he is certain that the soldier died because of the way he doubled up and dropped immediately. The bullet they used was also so large, and would have traveled at such a speed, that it would be impossible to survive such a hit, he said.

“There is no chance he survived,” Kovalskiy said.

The lack of confirmation that the shot was fatal is likely to lead to continued skepticism. When British sniper Craig Harrison broke the then-record in Afghanistan in 2009, killing two, the British military confirmed sightings of the corpses.

Kovalskiy says that online critics are incorrectly basing many of their calculations on the type of bullet used by the record-setting Canadian sniper.

A round is made of the actual projectile that hits a target and the casing that contains the explosive material that takes it there. Kovalskiy’s round was custom-made by a local gunsmith. It has a similar projectile to the Canadian round but a larger case that could pack more propellant, making it faster.

At a location in Kyiv, Kovalskiy and his spotter laid out their gun and bullets for inspection.

The long, thin gun is a specialist sniper rifle called the Lord of the Horizon, of which Kovalskiy’s is one of around 10. The rounds are 16 cm long.

The barrel was made by the U.S. company Bartlein Barrels and the scope comes from Japan. But the rest is Ukrainian, adding to local pride.

Kovalskiy and his spotter wonder why there is so much skepticism about a shot of this distance when targets, albeit stationary, have been achieved at these lengths several times in competitions such as the King of Two Miles in the U.S.

The two men are no ordinary snipers. Kovalskiy has been winning long-distance shooting competitions in Europe and North America for decades and first met his spotter at such competitions in Ukraine.

But this time, Kovalskiy hit a man, not an inanimate target. Unlike most soldiers, who may never see an enemy’s face let alone know if they have killed them, snipers head out seeking to kill people whom they can clearly see and generally have little doubt if they have taken a life.

Harrison, the former British sniper, said that the record is a heavy crown to wear.

Though he has since written a book about his experiences, the sniper says the actual record brought him misery for years. He was named by the British military without his permission, which led to threats against his life and that of his family, he said.

Harrison said sniping contributed to severe post-traumatic stress disorder that he has suffered after fighting in Kosovo, Iraq and Afghanistan.

“I will carry that last instant of their life in my mind forever. I know it will never leave me,” he wrote in his book.

Kovalskiy and his spotter say they have no regrets about killing Russians. Despite his age, the Ukrainian signed up as a sniper on the first day of Russia’s full-scale invasion.

“It doesn’t worry me a gram,” Kovalskiy said.

Ievgeniia Sivorka contributed to this article.

The Wall Street Journal, December 4, 2023

KYIV—The Ukrainian sniper had lain still for hours in near freezing temperatures when the command came to take the shot at a Russian soldier almost 2½ miles away. “You can,” his spotter said, and Vyacheslav Kovalskiy pulled his trigger.

The bullet took around nine seconds to reach its target, who doubled up and fell, according to a video of the shot reviewed by The Wall Street Journal. Kovalskiy and Ukraine say the shot set a new sniping distance record, breaking the previously acknowledged mark by more than 850 feet.

While combat hits such as this aren’t verified by a third-party adjudicator, the shot has offered Ukraine a morale boost when the country’s forces are struggling to make headway at the front line. A Ukrainian sniper, using a Ukrainian-made weapon and bullet, had broken the record. Sniping has played a prominent role in the war with Russia, where static front lines in a flat landscape suit the discipline, even as drones and mines change the way the marksmen operate.

Custom-made rounds used by Ukrainian snipers.

For conventional sniping, there are a lot of variables that are hard to quantify.

The macabre record was also a shot heard around the world of snipers, a group of highly skilled shooters who have long pushed the boundaries of just how far a bullet can travel with accuracy. Some are skeptical that Kovalskiy’s shot was a record.

To hit targets at ever-longer distances, snipers lean heavily on math, calculating a host of technical factors, from the air’s humidity to wind speed, temperature and the curvature of the earth. They also need a good rifle and a lot of luck.

On Nov. 18, Kovalskiy was already packing his rifle by the time the bullet reached its destination and a member of his team shouted that it was a hit. The shot was filmed and on reviewing the footage later, Kovalskiy and other snipers concluded it had been deadly.

“I was thinking that Russians would now know that is what Ukrainians are capable of,” Kovalskiy said, who hasn’t previously been named or spoken to the media.

“Let them sit at home and be afraid,” he added.

Several snipers and ballistics experts contacted by the Journal said that while the shot is possible with the equipment described, it would be hard to execute given the uncontrollable variables, not least the weather, that would have to be taken into account at such distances.

“For conventional sniping, there are so many variables that are hard to quantify, so the reality is anything over about 1,300 meters (about 4,265 feet) can be more luck than skill,” said Steve Walsh, a former U.S. Marines sniper instructor.

Kovalskiy’s shot hit around 12,470 feet, around a third longer than the Golden Gate Bridge. That distance would break a record of 11,600 feet set in 2017 by a member of the Canadian Special Forces in Iraq.

The 58-year-old former businessman’s journey to martial mythology started just before day break on Nov. 18, when he and his spotter, a partner who calculates distance, wind speed and other variables, set up positions across the river from a Russian military base in the Kherson region of east Ukraine.

The two men, who are part of a military counterintelligence division of the Security Service of Ukraine, or SBU, observed groups of Russian soldiers cutting wood. They considered these men’s ranks too low to shoot. At around noon, a group of five soldiers appeared and Kovalskiy noticed one instructing. He had his officer.

The spotter set to work. He used a laser to measure the distance to the soldiers. Using specialist software and meteorological data he concluded that there was a strong wind that would move the bullet around 200 feet from its trajectory. He calculated humidity and temperature, which affects how fast the bullet travels.

Even the spin and curvature of the earth has to be factored in for long-distance shots. By the time the bullet gets to its set distance, the target has already shifted with the earth’s rotation.

Ukrainian sniper Vyacheslav Kovalskiy packs up a custom made sniper rifle.

The scope on a Ukrainian sniper’s custom-made rifle.

Using all these variables, Kovalskiy tested a shot around 1,000 feet to the side of the target. It was a miss, the spotter told him.

They had got the wind speed wrong.

He quickly reset, reloaded and aimed.

“You have to (shoot) immediately because the wind changes constantly,” Kovalskiy said.

In video of the shot, the Russian officer can be seen gesticulating to men who had gathered around him. The spotter gave his usual command that he should fire.

“You can,” he said.

Kovalskiy pulled his trigger. The video shows a gap from shot to impact of around nine seconds, a period long enough that a target can have moved. U.S. ballistics expert Brad Millard timed the shot in footage and said that it was the correct time that this sort of bullet would take to hit 12,470 feet.

A sniper will aim their barrel above a target because gravity forces the bullet down. Kovalskiy’s shot was like a mini artillery shell, traveling over 330 feet above the level of the target before descending toward the unaware officer.

In the footage, the officer doubles up and falls and his men flee. The video ends.

The shot has been widely covered by Ukrainian news websites. It was also noted with pride by Ukrainian soldiers on the front line. In the Kreminna Forest in east Ukraine, a former sniper turned artilleryman said hearing the news was a “punch the air” moment.

“Everyone was talking about it,” he said.

Vyacheslav Kovalskiy holds a typical sniper round and a larger handmade custom round that he and his spotter used to shoot at a Russian soldier.

Ukraine needs a boost. A much-heralded counteroffensive has been stymied by stubborn Russian defense. The country has lost tens of thousands of soldiers and Russia continues to bomb civilian sites.

Countries in war often turn to combat legends to build morale, and countries in the former Soviet Union have a history of elevating the sniper to hero status. At the start of this war, Ukrainians traded stories of the “Ghost of Kyiv,” a Ukrainian jet-fighter pilot credited with shooting down several Russian planes. The Ukrainian military later said that rather than an individual pilot, the “Ghost of Kyiv” was meant as a composite symbolizing the combined heroism of its pilots.

Millard, the U.S. expert who designs software to test gun ballistics, says he doubts how the Ukrainian sniper team knows for sure that the officer was killed.

The shot hit its target in the chest or stomach area, Kovalskiy said. Having seen footage many times, he is certain that the soldier died because of the way he doubled up and dropped immediately. The bullet they used was also so large, and would have traveled at such a speed, that it would be impossible to survive such a hit, he said.

“There is no chance he survived,” Kovalskiy said.

The lack of confirmation that the shot was fatal is likely to lead to continued skepticism. When British sniper Craig Harrison broke the then-record in Afghanistan in 2009, killing two, the British military confirmed sightings of the corpses.

Kovalskiy says that online critics are incorrectly basing many of their calculations on the type of bullet used by the record-setting Canadian sniper.

A round is made of the actual projectile that hits a target and the casing that contains the explosive material that takes it there. Kovalskiy’s round was custom-made by a local gunsmith. It has a similar projectile to the Canadian round but a larger case that could pack more propellant, making it faster.

At a location in Kyiv, Kovalskiy and his spotter laid out their gun and bullets for inspection.

The long, thin gun is a specialist sniper rifle called the Lord of the Horizon, of which Kovalskiy’s is one of around 10. The rounds are 16 cm long.

The barrel was made by the U.S. company Bartlein Barrels and the scope comes from Japan. But the rest is Ukrainian, adding to local pride.

Kovalskiy and his spotter wonder why there is so much skepticism about a shot of this distance when targets, albeit stationary, have been achieved at these lengths several times in competitions such as the King of Two Miles in the U.S.

The two men are no ordinary snipers. Kovalskiy has been winning long-distance shooting competitions in Europe and North America for decades and first met his spotter at such competitions in Ukraine.

But this time, Kovalskiy hit a man, not an inanimate target. Unlike most soldiers, who may never see an enemy’s face let alone know if they have killed them, snipers head out seeking to kill people whom they can clearly see and generally have little doubt if they have taken a life.

Harrison, the former British sniper, said that the record is a heavy crown to wear.

Though he has since written a book about his experiences, the sniper says the actual record brought him misery for years. He was named by the British military without his permission, which led to threats against his life and that of his family, he said.

Harrison said sniping contributed to severe post-traumatic stress disorder that he has suffered after fighting in Kosovo, Iraq and Afghanistan.

“I will carry that last instant of their life in my mind forever. I know it will never leave me,” he wrote in his book.

Kovalskiy and his spotter say they have no regrets about killing Russians. Despite his age, the Ukrainian signed up as a sniper on the first day of Russia’s full-scale invasion.

“It doesn’t worry me a gram,” Kovalskiy said.

Ievgeniia Sivorka contributed to this article.

Last edited: