<span style="font-weight: bold">L-3 Ground Panoramic Night Vision Goggle</span>

Night vision goggles offer operators an incredible advantage on the modern battlefield. The ability to observe and engage the enemy without them even being aware of your presence is a formidable weapon. Image intensification technology has come a long way since the massive tank-mounted “active IR” devices of World War II, becoming smaller, more portable, and advanced for the individual Warfighter. The Global War on Terror has accelerated the progress of night vision technology and its application. Hundreds of thousands of U.S. and Coalition troops have gone downrange wearing some of the most advanced and varied image intensifiers ever seen (or not seen as it were).

The onset of the war in Afghanistan and later, Iraq, has presented Warfighters with a myriad of combat zones that present different challenges to the operator under goggles. Wide open desert, high altitude mountains, urban areas, and even tropical zones all have different requirements. Enemy fighters have also quickly adapted to the good-guys’ strikingly more advanced technology. As enemy tactics evolved, so to has the equipment used to kill them. Night vision devices have begun incorporating fusion technology, traditional image intensifier technology with thermal overlays. Individual goggles have also begun incorporating awareness applications that help link the boots on the ground with the eye in the sky. These types of advancements have greatly increased the Warfighters’ ability to kill bad guys, ensuring he/she has the most information available to put them ahead of the power curve. But, even with all these advancements, night vision goggles are not magic and they do not automatically give the good guys super powers. As with all other weapon systems, it is paramount for the operator to know and understand the strengths and weaknesses of the device. Attempting to deploy a weapon system outside of its core competency can have disastrous results. Of course, this does not mean that Warfighters always play it safe. Let’s face it; this is dangerous work. We ain’t making cupcakes. By pushing the limits of available technology, operators are able to develop new TTP’s and help influence the development of new technology that better addresses ever developing field conditions.

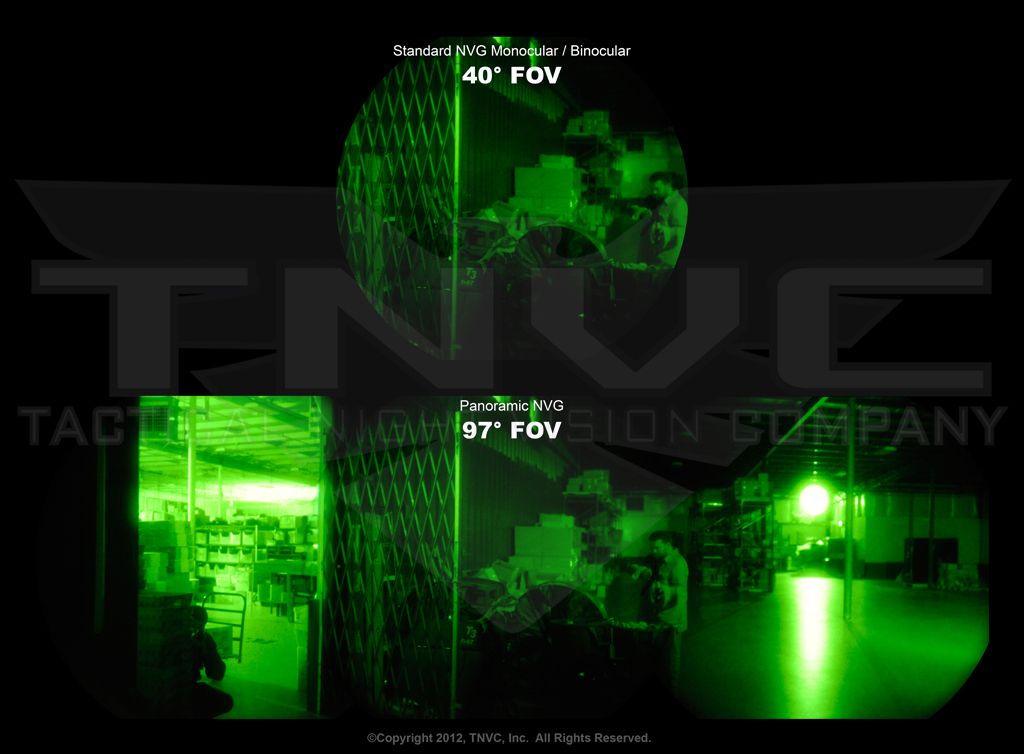

One of the most notable limitations of current night vision goggles is the relatively small field of view (FOV) they offer. Traditional devices give the wearer a small 40° FOV. This is like viewing the world through a toilet paper tube. The image intensifier tube gives the wearer an almost day-like view in the darkness, but only through a confined objective. While this narrow FOV is very useable in many areas, it does require a lot of training to apply properly and safely. For instance, the operator must keep his/her head on the proverbial swivel, scanning constantly to take in as much of the environment as possible through the goggle. The scanning must be done in a smooth, controlled manner to avoid missing anything. Depth perception is also an issue. We have two eyes which allow us to achieve instant near to far focus changes and keep us from tripping over obstacles at our feet or trying to grab a door knob that is ten yards away. The ubiquitous AN/PVS-14, the standard issue NVG for U.S. Forces, has many benefits in a monocular configuration, but depth perception is not one of them. The world flattens out in the eye of a monocular-equipped operator. This is why pilots flying under goggles must wear dual-tube binoculars instead. It is also why Special Operations Forces (SOF) operators on the ground prefer running dual tubes. The ability to more quickly and safely traverse terrain and negotiate obstacles is incredibly beneficial to the high speed nature of SOF missions. But, regardless of whether the wearer is running one tube or two, they are still limited by a 40° FOV.

While the 40° FOV can be used very effectively with lots of training, there are certain applications where it just is not a good idea. One of the main things would-be operators need to understand is when to forego the advantage of night vision goggles in favor or traditional white light. Running goggles is not anything like the movies where a technology-covered super operator kicks in the door or rappels through the window wearing a goggle and quickly clears a complex of enemy fighters inside and out, all while seeing the world as if conditions were normal. The fact is; Close Quarters Battle (CQB) is not a good place to run you’re AN/PVS-14 or other traditional goggle. It is just way too fast with operators needing to instantaneously take in every detail of a room, process the information as they move to their point of domination in the room and cover their sector, all while identifying possible threats, determining if they are threats, and taking appropriate action. The idea is to get as many guns into the room and completely dominate the situation with overwhelming force. And, operators can only do that by taking in the most information in the shortest amount of time; often fractions of a second. The bottom line is that bad guys need to be processed within seconds of a team entering a room and this is almost impossible to do safely under traditional goggles because the amount of information taken in through 40° is too small and too slow… Until now.

L-3 Warrior Systems, the night vision division of L-3, has developed and fielded one of the biggest innovations in night vision technology with the Ground Panoramic Night Vision Goggle (GPNVG-18). While this goggle doesn’t add thermal fusion or give the operator instant linkup to orbiting drones, it does address the all-important FOV limitation. Recently, TNVC was presented with an opportunity to play with this unique goggle. While I will not divulge any technology beyond the open source information already available, I will provide you a closer look at one of the most innovative and out-of-the-box NVG’s available to our most elite warriors.

The purpose of the GPNVG-18 is to provide the operator more information under goggles, allowing him to more quickly move through the OODA Loop (Observe, Orient, Decide, Act). The most striking feature of the GPNVG-18 is the presence of four separate image intensifier tubes with four separate objective lenses arrayed in a panoramic orientation. The center two lenses point forward like traditional dual-tube goggles, giving the operator more depth perception, while two more tubes point slightly outward from the center to increase peripheral view. The two tubes on the right and the two on the left are spliced at the eyepieces. The operator sees the two center tubes somewhat overlapping the two outer tubes to produce an unprecedented 97° FOV. This is an absolute game-changer for the SOF community. The two right and two left tubes are housed in merged assemblies and are hung from a bridge similar to ANVIS goggles, giving operators interpuplliary adjustment options. They can also be easily removed and operated as independent handheld viewers. The Bridge assembly features fore/aft adjustment on a ratchet system and can come configured from the factory in two different variants for different helmet mount setups: Ball Detent (ANVIS) or Dovetail (BNVS).

The GPNVG-18 is powered by a remote battery pack, tethered to the unit via a standard ANVIS cable. It comes with a pack that accepts four 3-Volt CR123A batteries that tend to power the unit for about thirty hours (in my trial). The GPNVG-18 can be powered for a shorter amount of time if mounted in the new Wilcox Panoramic Mount designed for a certain military unit. The remote battery pack provides a secondary function as a counterweight, which is needed considering the goggle weighs about 27 ounces.

The unit we got to play with was the ANVIS style goggle. Like actual ANVIS goggles, the GPNVG-18 turns off when the goggle is flipped up. Regardless of position, the operator must become used to the width of the device. It obviously protrudes further on both sides than traditional goggles, so care must be given when donning or doffing various mission-essential items, like slings. The goggle has a width of about 8.5”, so stability is a must. That is why it is critical to use hooked bungees on the helmet to make sure it is not bouncing around. Even so, there is very little play in these goggles. One of the issues that plague bridge-type systems is the inherent wobble/rattle found in the connection between the tube housings and the bridge itself. I noticed surprisingly little wobble in the GPNVG-18.

Night vision goggles offer operators an incredible advantage on the modern battlefield. The ability to observe and engage the enemy without them even being aware of your presence is a formidable weapon. Image intensification technology has come a long way since the massive tank-mounted “active IR” devices of World War II, becoming smaller, more portable, and advanced for the individual Warfighter. The Global War on Terror has accelerated the progress of night vision technology and its application. Hundreds of thousands of U.S. and Coalition troops have gone downrange wearing some of the most advanced and varied image intensifiers ever seen (or not seen as it were).

The onset of the war in Afghanistan and later, Iraq, has presented Warfighters with a myriad of combat zones that present different challenges to the operator under goggles. Wide open desert, high altitude mountains, urban areas, and even tropical zones all have different requirements. Enemy fighters have also quickly adapted to the good-guys’ strikingly more advanced technology. As enemy tactics evolved, so to has the equipment used to kill them. Night vision devices have begun incorporating fusion technology, traditional image intensifier technology with thermal overlays. Individual goggles have also begun incorporating awareness applications that help link the boots on the ground with the eye in the sky. These types of advancements have greatly increased the Warfighters’ ability to kill bad guys, ensuring he/she has the most information available to put them ahead of the power curve. But, even with all these advancements, night vision goggles are not magic and they do not automatically give the good guys super powers. As with all other weapon systems, it is paramount for the operator to know and understand the strengths and weaknesses of the device. Attempting to deploy a weapon system outside of its core competency can have disastrous results. Of course, this does not mean that Warfighters always play it safe. Let’s face it; this is dangerous work. We ain’t making cupcakes. By pushing the limits of available technology, operators are able to develop new TTP’s and help influence the development of new technology that better addresses ever developing field conditions.

One of the most notable limitations of current night vision goggles is the relatively small field of view (FOV) they offer. Traditional devices give the wearer a small 40° FOV. This is like viewing the world through a toilet paper tube. The image intensifier tube gives the wearer an almost day-like view in the darkness, but only through a confined objective. While this narrow FOV is very useable in many areas, it does require a lot of training to apply properly and safely. For instance, the operator must keep his/her head on the proverbial swivel, scanning constantly to take in as much of the environment as possible through the goggle. The scanning must be done in a smooth, controlled manner to avoid missing anything. Depth perception is also an issue. We have two eyes which allow us to achieve instant near to far focus changes and keep us from tripping over obstacles at our feet or trying to grab a door knob that is ten yards away. The ubiquitous AN/PVS-14, the standard issue NVG for U.S. Forces, has many benefits in a monocular configuration, but depth perception is not one of them. The world flattens out in the eye of a monocular-equipped operator. This is why pilots flying under goggles must wear dual-tube binoculars instead. It is also why Special Operations Forces (SOF) operators on the ground prefer running dual tubes. The ability to more quickly and safely traverse terrain and negotiate obstacles is incredibly beneficial to the high speed nature of SOF missions. But, regardless of whether the wearer is running one tube or two, they are still limited by a 40° FOV.

While the 40° FOV can be used very effectively with lots of training, there are certain applications where it just is not a good idea. One of the main things would-be operators need to understand is when to forego the advantage of night vision goggles in favor or traditional white light. Running goggles is not anything like the movies where a technology-covered super operator kicks in the door or rappels through the window wearing a goggle and quickly clears a complex of enemy fighters inside and out, all while seeing the world as if conditions were normal. The fact is; Close Quarters Battle (CQB) is not a good place to run you’re AN/PVS-14 or other traditional goggle. It is just way too fast with operators needing to instantaneously take in every detail of a room, process the information as they move to their point of domination in the room and cover their sector, all while identifying possible threats, determining if they are threats, and taking appropriate action. The idea is to get as many guns into the room and completely dominate the situation with overwhelming force. And, operators can only do that by taking in the most information in the shortest amount of time; often fractions of a second. The bottom line is that bad guys need to be processed within seconds of a team entering a room and this is almost impossible to do safely under traditional goggles because the amount of information taken in through 40° is too small and too slow… Until now.

L-3 Warrior Systems, the night vision division of L-3, has developed and fielded one of the biggest innovations in night vision technology with the Ground Panoramic Night Vision Goggle (GPNVG-18). While this goggle doesn’t add thermal fusion or give the operator instant linkup to orbiting drones, it does address the all-important FOV limitation. Recently, TNVC was presented with an opportunity to play with this unique goggle. While I will not divulge any technology beyond the open source information already available, I will provide you a closer look at one of the most innovative and out-of-the-box NVG’s available to our most elite warriors.

The purpose of the GPNVG-18 is to provide the operator more information under goggles, allowing him to more quickly move through the OODA Loop (Observe, Orient, Decide, Act). The most striking feature of the GPNVG-18 is the presence of four separate image intensifier tubes with four separate objective lenses arrayed in a panoramic orientation. The center two lenses point forward like traditional dual-tube goggles, giving the operator more depth perception, while two more tubes point slightly outward from the center to increase peripheral view. The two tubes on the right and the two on the left are spliced at the eyepieces. The operator sees the two center tubes somewhat overlapping the two outer tubes to produce an unprecedented 97° FOV. This is an absolute game-changer for the SOF community. The two right and two left tubes are housed in merged assemblies and are hung from a bridge similar to ANVIS goggles, giving operators interpuplliary adjustment options. They can also be easily removed and operated as independent handheld viewers. The Bridge assembly features fore/aft adjustment on a ratchet system and can come configured from the factory in two different variants for different helmet mount setups: Ball Detent (ANVIS) or Dovetail (BNVS).

The GPNVG-18 is powered by a remote battery pack, tethered to the unit via a standard ANVIS cable. It comes with a pack that accepts four 3-Volt CR123A batteries that tend to power the unit for about thirty hours (in my trial). The GPNVG-18 can be powered for a shorter amount of time if mounted in the new Wilcox Panoramic Mount designed for a certain military unit. The remote battery pack provides a secondary function as a counterweight, which is needed considering the goggle weighs about 27 ounces.

The unit we got to play with was the ANVIS style goggle. Like actual ANVIS goggles, the GPNVG-18 turns off when the goggle is flipped up. Regardless of position, the operator must become used to the width of the device. It obviously protrudes further on both sides than traditional goggles, so care must be given when donning or doffing various mission-essential items, like slings. The goggle has a width of about 8.5”, so stability is a must. That is why it is critical to use hooked bungees on the helmet to make sure it is not bouncing around. Even so, there is very little play in these goggles. One of the issues that plague bridge-type systems is the inherent wobble/rattle found in the connection between the tube housings and the bridge itself. I noticed surprisingly little wobble in the GPNVG-18.