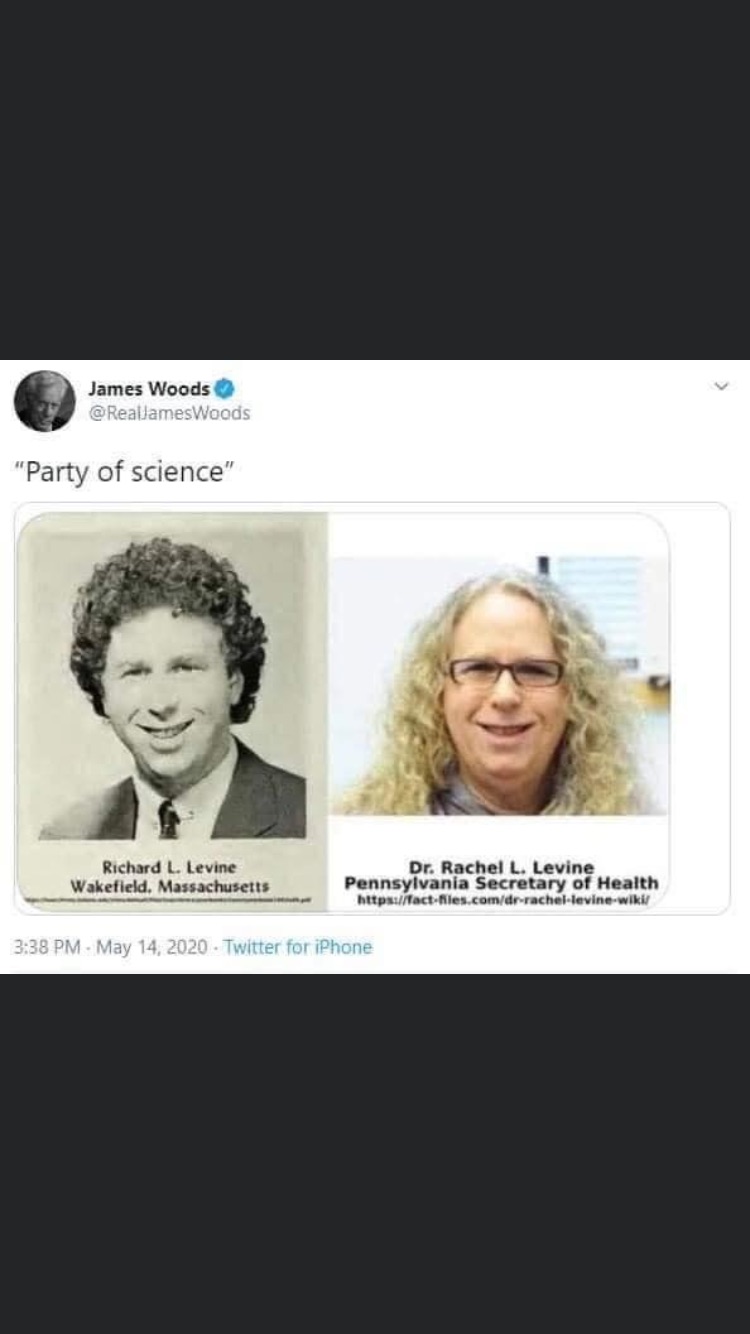

These are the people we are supposed to be taking health directives from ? The crypt keeper ^^^ and a insane dude that wants to chop off his wiener. “It’s a madhouse“

Join the Hide community

Get access to live stream, lessons, the post exchange, and chat with other snipers.

Register

Download Gravity Ballistics

Get help to accurately calculate and scope your sniper rifle using real shooting data.

Install the app

How to install the app on iOS

Follow along with the video below to see how to install our site as a web app on your home screen.

Note: This feature may not be available in some browsers.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Maggie’s Socially UNacceptable Humor

- Thread starter Duc

- Start date

It's kina like Big Bird boned a corpse, and this thing is what fell out . . .she appears to have been dead for some time. View attachment 7327703

Not

Even

With

Your

Dick!

No way!

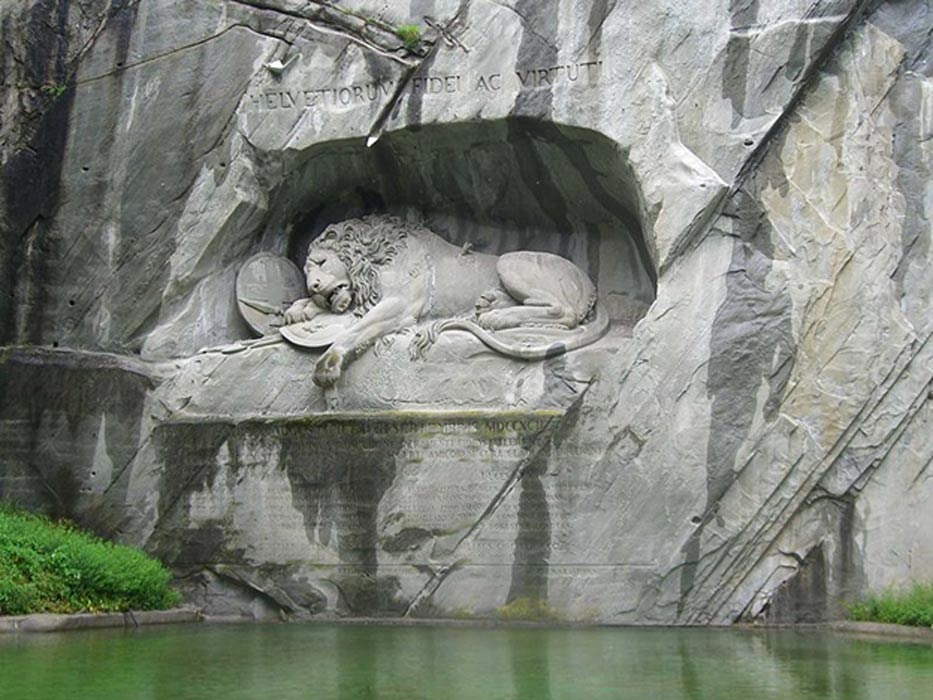

I'm sure several of you already know this, but this is carved into the face of the rock in Lucerne, Switzerland. The artist did so as a tribute to his friends and compatriots who were killed in a battle. That opening is roughly 15-20 feet across, for scale.

I wonder if those would sell on a T Shirt?LA street art is spot on. View attachment 7328119View attachment 7328116

It is in a pretty little park. Luzern, as with most Swiss cities and towns, is beautiful.I'm sure several of you already know this, but this is carved into the face of the rock in Lucerne, Switzerland. The artist did so as a tribute to his friends and compatriots who were killed in a battle. That opening is roughly 15-20 feet across, for scale.

Brad Thor did a book called “The Lions of Lucerne”. Wonder if it had anything to do with that? Pretty good book by the way.

Brad Thor did a book called “The Lions of Lucerne”. Wonder if it had anything to do with that? Pretty good book by the way.

Thor's book title is a reference to the statue, yes; but a completely unrelated story, obviously.

Wikipedia:

From the early 17th century, a regiment of Swiss Guards had served as part of the Royal Household of France. On 6 October 1789, King Louis XVI had been forced to move with his family from the Palace of Versailles to the Tuileries Palace in Paris. In June 1791 he tried to flee to Montmédy near the frontier, where troops under royalist officers were concentrated. In the 1792 10th of August Insurrection, revolutionaries stormed the palace. Fighting broke out spontaneously after the Royal Family had been escorted from the Tuileries to take refuge with the Legislative Assembly. The Swiss Guards ran low on ammunition and were overwhelmed by superior numbers. A note written by the King half an hour after firing had commenced has survived, ordering the Swiss to retire and return to their barracks.[4] Delivered in the middle of the fighting, this was only acted on after their position had become untenable.[5]

Of the Swiss Guards defending the Tuileries, more than six hundred were killed during the fighting or massacred after surrender. An estimated two hundred more died in prison of their wounds or were killed during the September Massacres that followed. Apart from about a hundred Swiss who escaped from the Tuileries, the only survivors of the regiment were a 300 strong detachment which, with the King's authorization, had been sent to Normandy to escort grain convoys a few days before August 10.[6] The Swiss officers were mostly amongst those massacred, although Major Karl Josef von Bachmann — in command at the Tuileries — was formally tried and guillotined in September, still wearing his red uniform coat. Two surviving Swiss officers achieved senior rank under Napoleon.

Memorial

The initiative to create the monument was taken by Karl Pfyffer von Altishofen, an officer of the Guards who had been on leave in Lucerne at that time of the fight. He began collecting money in 1818. The monument was designed by Danish sculptor Bertel Thorvaldsen, and hewn in 1820–21 by Lukas Ahorn, in a former sandstone quarry near Lucerne. Carved into the cliff face, the monument measures ten metres in length and six metres in height.

The monument is dedicated Helvetiorum Fidei ac Virtuti ("To the loyalty and bravery of the Swiss"). The dying lion is portrayed impaled by a spear, covering a shield bearing the fleur-de-lis of the French monarchy; beside him is another shield bearing the coat of arms of Switzerland. The inscription below the sculpture lists the names of the officers and gives the approximate numbers of soldiers who died (DCCLX = 760), and survived (CCCL = 350).[7]

The monument is described by Thomas Carlyle in The French Revolution: A History.[8] The pose of the lion was copied in 1894 by Thomas M. Brady (1849–1907)[9] for his Lion of Atlanta in the Oakland Cemetery in Atlanta, Georgia.

Mark Twain on the monument

The Lion lies in his lair in the perpendicular face of a low cliff—for he is carved from the living rock of the cliff. His size is colossal, his attitude is noble. His head is bowed, the broken spear is sticking in his shoulder, his protecting paw rests upon the lilies of France. Vines hang down the cliff and wave in the wind, and a clear stream trickles from above and empties into a pond at the base, and in the smooth surface of the pond the lion is mirrored, among the water-lilies.

Around about are green trees and grass. The place is a sheltered, reposeful woodland nook, remote from noise and stir and confusion—and all this is fitting, for lions do die in such places, and not on granite pedestals in public squares fenced with fancy iron railings. The Lion of Lucerne would be impressive anywhere, but nowhere so impressive as where he is.

— Mark Twain, A Tramp Abroad, 1880

One of my favorite cities on the planet...beautiful city, history and a lot of fun bars along the river to meet peopleIt is in a pretty little park. Luzern, as with most Swiss cities and towns, is beautiful.

HOLY FUCK this needs to be tweeted and retweeted. That is the most epic shit I've seen so far...

MAGA/KAG

III

Once when I was about five, I went dumpster diving with a friend because that's what 5yos do. It was the type of dumpster you loaded from the side, not top. The trash truck came while we were in it and we got dumped into the trash truck. I wanted to crawl out he way we got dumped in but the kid I was with was in full panic mode and just started crying/screaming. About that time I noticed the 'roof' coming down and pointed it out to my friend. Told him to follow me out but he just stood there crying. Well lucky for him, the truck driver and his assistant heard him crying and shut down the truck. Next thing I know they're opening the rear doors to reveal us standing there. The shock on their face I can still remember. I'm 51 now. They pulled us out and took us to our respective apartments. The whole way to our apartment I was begging him not to tell my mom. I was grounded for two weeks. Not sure if that was before or after I stuck a butter knife in an outlet and blew the breaker, freaking my mom out. Grounded for two weeks for that too. I was a curious little fucker.

Jeebuz, yer dangerous......Once when I was about five, I went dumpster diving with a friend because that's what 5yos do. It was the type of dumpster you loaded from the side, not top. The trash truck came while we were in it and we got dumped into the trash truck. I wanted to crawl out he way we got dumped in but the kid I was with was in full panic mode and just started crying/screaming. About that time I noticed the 'roof' coming down and pointed it out to my friend. Told him to follow me out but he just stood there crying. Well lucky for him, the truck driver and his assistant heard him crying and shut down the truck. Next thing I know they're opening the rear doors to reveal us standing there. The shock on their face I can still remember. I'm 51 now. They pulled us out and took us to our respective apartments. The whole way to our apartment I was begging him not to tell my mom. I was grounded for two weeks. Not sure if that was before or after I stuck a butter knife in an outlet and blew the breaker, freaking my mom out. Grounded for two weeks for that too. I was a curious little fucker.

Or bang 30 guys in a month on Tinder

Ask the 30 to pay for 1/2 of the Abo-bo at planned parenthood

My wife just found out she's adopted and she is devastated. She kept asking "Why didn't they want me?"

I comforted her while she was crying and after a while she asked me to make love to her which led to more tears.

On reflection, banging her from behind and yelling "Who's your daddy?" was a little insensitive.

I comforted her while she was crying and after a while she asked me to make love to her which led to more tears.

On reflection, banging her from behind and yelling "Who's your daddy?" was a little insensitive.

I swear my drunken self manages to find the stupidest shit to laugh at on YouTube.

Once again, we arrive at the Jewish problem.

He is just north of where I'm at. Opelousas LA. Was a life long Democrat and switched parties a few years ago. WE need more people like him to stand up! Great job!thats awesome

It wasn't like this when my kiddo's watched.

Smell like shit and have brown spots?

It wasn't like this when my kiddo's watched.

The autism character!

Similar threads

- Replies

- 10

- Views

- 1K